Jun 4, 2020 07:29 UTC

| Updated:

Jun 17, 2020 at 20:38 UTC

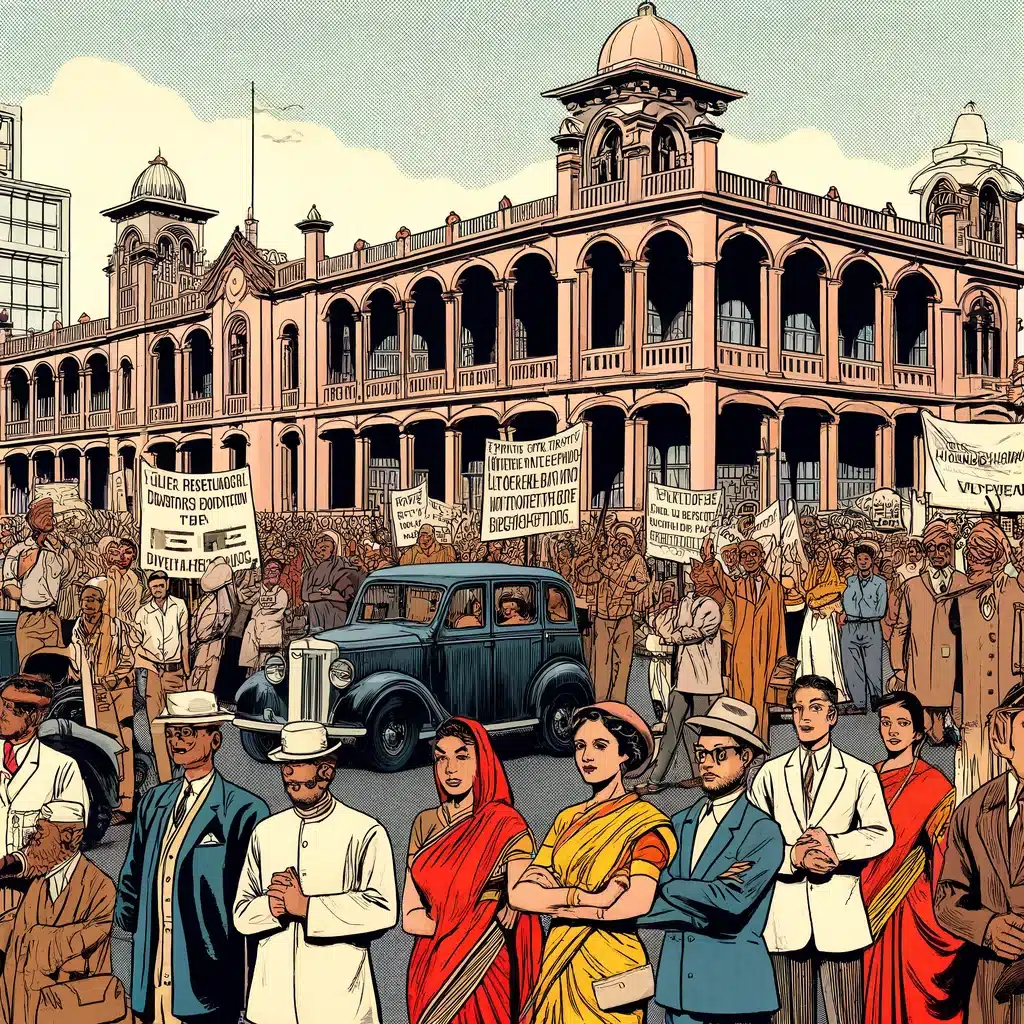

The dichotomy between Human Right Violations and Corporate Social Responsibility in India

By Mohammad Adil Ansari & Shivani Chauhan

Abstract

There is an inherent contradiction between corporate law mechanics and human rights. The framework of a corporate which manifests a capitalist motto at its roots is driven on a scale of capital profit rather than welfare considerations of the public at large, often entailing little or no accountability to the implications to its human rights violations. The body of corporate law, until the Companies Act 2013 was drafted, was prima facie aimed to serve the efficiency of the corporate entity and did not take into account any human rights or environmental perspective to its regulatory and accountability framework. The inclusion of Corporate Social Responsibility provision and rules, as well as growing demand for provisions for Corporate Criminal Liability, clearly demonstrate the incompatibility between the Corporate Law framework as well as the Human Rights and the need to reach a level of balance. The recent attempts to reconcile this antagonist pair into reaching a degree of homeostasis through applaudable is grossly insufficient as well as inherently flawed requiring a restructuring of the entire regulatory and redressal framework. The introduction of CSR doctrine, originally crafted to serve as an instrument for socio-economic welfare has in fact been prostituted and reduced to a Public Relations exercise and an apparatus to camouflage corporation’s gross human rights and environmental norms violations.

The paper shall examine the dynamics of the dichotomy between human right violations and Corporate Social Responsibility in the Indian context, illuminating the legislative and policy loopholes to check human rights violations by corporations, with a focus on the emerging demand for a legal framework for corporate criminal liability.

Introduction

According to Global Justice Now, in 2016, out of the top 100 economies in the worlds, only 31 are countries while the rest 69 are corporations. [3] As of now the influence of the corporate sector is dominating the global demography is expanding at an alarming rate, while a regulatory framework to hold them accountable for human rights violation is still in its nascent stage. In the wake of Washington Consensus of 1989 which introduced the world to Liberalisation, Privatisation and Globalisation, we reinstated the global unhindered capitalism in the form of multinational corporate giants emerging and dominating the world economy, mostly at the cost of the developing nations and vulnerable and marginalised population. Through negotiations and often through coercive policies of IMF and World Bank, soon the entire world was transformed into a free market, the economic definition of a ‘jungle raj’, where the big fish (Multinational Corporation) is at liberty to devour on small fish (developing nations, small and cottage industries, marginalised and traditional economies and populations).

With the traditional study of economics being confined on tracking the well being of a population being directly proportional to its capital generation and increase in economic variables, the very parameter of consideration of the welfare of a population by a State was flawed and collaterally served the interests of corporations. While the economists and theorists were too late to acknowledge such a flaw, any attempt for a much more relevant and justifiable parameter was not made until 1990 Human Development Report which introduced the concept of Human Development Index. A better more elaborate and qualitative concept in the form of ‘Gross National Happiness’ was recognised much recently, with the first World Happiness Report being published in 2012. But such parameters being of recent origin and of a qualitative nature have been grossly overlooked by countries, which still stipulate upon traditional quantitative parameters such as GDP, GNP and NNP to approach the wellbeing of their state.

Lack of International Instruments

Lacking a theoretical validity to it earlier, countries have overlooked the qualitative and welfare aspects of their national economy for most part of the history. And even today after a proper academic soundness and international validity to qualitative concepts such as ‘Development Index’ and ‘National Happiness’, still chose to renounce the same, in spite of being faced with global crisis of terrorism, environmental degradation, human trafficking and other global challenges. The most remarkable and recent example is of the United States bailing out of 2015 UNFCCC Paris Agreement in 2017 to boost its corporations. With such a trend in operation, we are destined to suffer more human rights violations at the behest of corporations.

With regards to the culpability of the corporations towards any human rights violations, we still lack a proper redressal mechanism and a regulatory framework. The 2011 UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the UN Global Compact programme initiative, due to their voluntary and non-binding application on states and corporations are impotent in approach and effect. The OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, which offer a degree of accountability by setting up national redressal and enforcement agencies in the form of National Contact Point (NCP), is limited to its 36 member-states, of which India is not a party.

The Indian Approach

In his article “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits”, Milton Friedman has rightly attributed that the basic tenet of any corporation is to cater to the interests of its shareholders and to enhance their wealth. The mechanism of the corporation is not concerned with how the end profit shall be realised but as to how it shall be generated within least costs. It is notable at this point that the greater the exploitation, the lesser is the cost. Compliance with human rights and environment protection norms call for additional costs, a burden the corporations are inclined to evade. Rather corporations have a history to thrive on gross exploitation of human rights. From the plight of the working class during the Industrial age to India’s drainage of wealth by the East India Company to the examples of funding of wars and internal conflict in recent history by corporations, the trend points that corporations tend to thrive tremendously in demographics ridden with conflict. The recent instances being of a number of high profile UK companies, including M&S and Asos capitalizing over the Syrian conflict, by exploiting child refugees from Syria working in very poor and inhumane conditions for clothing suppliers based in Turkey. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States was also driven by an agenda to take control of its rich oil reserves to enhance the global hegemony of US industries in the world economy in pursuit of the Carter Doctrine.

The Companies Act, 2013 had made an attempt to reform this ‘mechanical pursuit’ by shifting its paradigm to make corporations responsible for the welfare of the population. Section 166(2) of the Companies Act, 2013 has made it an obligation upon the directors of a company to consider the best interests of the community, its employees and environment while fulfilling their duty to work for the best interest of the company. Section 135 along with Corporate Social Responsibility Rules, 2014, obligates ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ Policy on enterprises having net worth of 500 crore rupees or above. For the purpose of the evaluation of the proposed dichotomy, we shall be confined therefore, to these provisions only.

In a vacuum of any binding international framework as well as a national redressal legislation (concerning India), the concept of ‘Corporate Social Responsibility’ (CSR) is the only legislative string which mandate a notion of responsibility towards population, by the corporations (the labour laws being only limited to the employees of the corporation). This recent corporate invention of CSR has been tremendously exaggerated by both the governments as well as the corporate world, as a watershed in achieving homeostasis equilibrium between the corporate profit machinery and securing socio-economic welfare. The basic motive, cited by the State, behind bringing corporation under the ambit of such social welfare scheme, was to minimize the economic disparity between the richest and the poorest of the community. By making corporations liable for the social welfare schemes, an attempt was made to disburse a part of corporation’s profit towards economic equality and at the same time to reduce the State’s own liabilities. Going through the plethora of articles written on the credibility of such an invention, it is quite conspicuous to draw a string of unanimous agreement in its favour.

On record the Financial Year 2015-16 witnessed a 28 percent growth in CSR spending in comparison to the preceding year. Listed companies in India spent US$1.23 billion in various programs ranging from educational programs, skill development, social welfare, healthcare, and environment conservation. The Prime Minister’s Relief Fund saw an increase of 418 percent to US$103 million in comparison to US$24.5 million in 2014-15. Thus, the concept has gained critical acclaim to be at the least, a step into the right direction.

But on tracking the effect and benefits of such a corporate benevolence trend, through several reports, namely, 2011 UN Report On The Issue Of Human Rights And Transnational Corporations And Other Business Enterprises, the ‘2014 UN Report of the Special Rapporteur On Extreme Poverty And Human Rights’ as well as all the Oxfam reports with the 2018 ‘Reward Work, Not Wealth’ report, being the latest in this line-up, and several other independent reports, a contrary picture appears on the surface. The CSR provision, as a matter of fact, has been exploited to serve as a ‘Public Relations Tool’ by the corporations to mask their human rights and environmental norm violations by ‘Greenwashing’. The author would substantiate the analysis with few examples:

The Vedanta Sterlite Case

Vedanta group is one of the largest contributors to India’s CSR activity with a targeted investment of Rs 285 crore in 2018. The company has often been accused by both international media and environmentalists of trying to whitewash its flaunting of environment and human rights norms. Its recent surge in Tamil Nadu, were its Sterlite Copper unit was surrounded in major controversies. In response to the plant causing serious environmental and industrial accidents the Madras High Court in 2010 directed the plant to shut down. However, on appeal by the Company the Supreme Court passed an interim order staying the High Court order.

On 24 March 2018 a protest broke against the expansion of the plant and the hazardous environmental and health issues caused by the plant such as cancer, respiratory diseases, birth of children with congenital disorders etc. The company despite being declined the permission to expand its plant, by the Tamil Nadu Pollution Control Board, illegally continued construction of the plant. This triggered the anger of many people and led to a peaceful protest which lasted more than 100 days. The police on the hundredth day eventually opened fired at the protestors killing around 10 people.

Controversies surrounding Vedanta’s flaunting of environmental and human rights norms have now snowballed into an international human rights and tribal displacement issue.

The Kitex Take-Over of Kizhakkambalam Panchayat

In response to the refusal to grant the Kitex group the license to operate its bleaching plant and effluent plant by the panchayat, Twenty20, the corporate social responsibility wing of the Rs 1,500-crore textile major, Anna-Kitex group, jumped into the political arena, winning 17 of the 19 seats of the Kizhakkambalam panchayat. It was the first instance in the country that a corporate house became a direct participant in electoral democracy, subsequently winning and taking over control of a panchayat in the process. The Twenty20 group utilized its CSR activities such as building of houses and toilets, drinking water scheme, electrification, regulating of ration shops etc. for gaining a political mileage against the contesting candidates. This brazen “takeover of democracy” has many public intellectuals worried as it sets a dangerous precedent.

The 2018 Oxfam Report, in fact, clearly forecasts the hollowness and gross inadequacy of such corporate induced philanthropy. The Report explicitly announces in its opening pages, that 82% of all wealth created in the preceding year went to the top 1% while the bottom 50% saw no increase at all. In India, 73% of the wealth generated in 2017 went to the richest one percent, while 67 crore Indians who comprise the poorest half of the population saw only 1% increase in their wealth. In the last 12 months the wealth of this elite group increased by Rs 20,913 billion. This amount is equivalent to total budget of Central Government in 2017-18. The report outlines the mechanical profit pursuit of corporation at the cost of workers’ pay and conditions to be the key factor contributing towards this rising inequality. These include the erosion of workers’ rights, the excessive influence of big business over government policy-making and the relentless corporate drive to minimize costs in order to maximize returns to shareholders.

Thus, the arguments in favour of corporate social responsibility to make corporates as agents of wide scale poverty elevation and social welfare schemes fell flat on the face. Corporate sustainability which forms the core of this concept refers to the role that companies can play in meeting the agenda of sustainable development and entails a balanced approach to economic progress, social progress and environmental stewardship. The trend, as validated by in 2018 Oxfam Report and abovementioned instances, as a matter of fact shows a diametrically opposite picture in physical world. Thus, rather than serving as a tool for the upholding of the environmental and human rights, the provisions have been prostituted to serve as a mask to camouflage their exploitation.

Conclusion and Suggestions

The root cause of the dichotomy between human rights vis-à-vis corporate social responsibility in India is the Indian perception that CSR is an adequate redressal and compensatory measure against monstrous corporate transgressions. The authors refute such a stand, by categorically stating that a right always correlate an adjoining duty and its violation gives rise to a liability. A mandated philanthropic endeavour therefore cannot serve as a license to encroach upon anyone’s human rights. A proper redressal system is the need of the hour.

The only redressal mechanism in operation today is of judicial invention in the form of a Public Interest Litigation. The innovation of ‘Absolute liability’ as propounded in the case of M.C Mehta v. Union of India, [4] being the only resort in such cases. The principle while holding relevance in cases of big industrial disasters is contestable and unfeasible in its application in cases of biopiracy, infringement of right to access to water by privatisation of water bodies, labour law violations, medical trials on vulnerable groups by pharma industries whose limited access to knowledge and justice prevents recognition of the abuse of their rights, etc. Thus, emphasis on Corporate Criminal Liability’ is the need of the hour.

The doctrine of corporate criminal liability was given validation in India, in the case of Standard Chartered Bank v. Directorate of Enforcement5 where the court observed, “A company is liable to be prosecuted for the criminal offence although act may be committed through its agent.” The approach was later reframed and redesigned in the 2010 landmark judgment of Iridium India Telecom Ltd. V. Motorola Inc & ors. [6] The court held that despite being a legal fiction, a company can be said to possess mens rea required to commit a crime. But the problem arose regarding the inadequacy of most penal provisions which fail to take into account legal fictional entities. Thus the 41st Law Commission gave a report suggesting amendment in the penal provisions and providing for substitution of imprisonment with fine in case of offender being a body corporate. But the Legislature till date has failed to take into account those recommendations.

Parliament must introduce laws and provisions which implicate strict or absolute liability upon corporations depending upon the nature of the offence. The Corporate Manslaughter and Corporate Homicide Act 2007 of United Kingdom, as well as the OECD Experiment of National Nodal Points, can serve as a reference for this purpose. An addition requirement of enforcing dictates of the National Voluntary Guidelines for Social, Environmental and Economic Responsibilities of Business (NVGs) and 2011 UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights warranted with some form of legal penalty, can further serve the purpose of bringing corporations under judicial scrutiny and social accountability.

Our Constitution explicitly mandates the State to be directly responsible for the welfare of the people and protection of their human rights under Article 38, 39, 39A, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 and 48A. With due acknowledgment to the positive impact of the CSR Policy, it must not be used as an apparatus for abandonment of State’s responsibilities, else incidents such as Kizhakkambalam panchayat takeover shall become more and more frequent, thereby threatening the resurface of the colonization tendencies of the corporations.

It is the fundamental right of everyone to have a government that works in the public interest and not for the benefit of a few. When in matters of public policy and governmental decisions, the pivot is directed by the interest of business and corporation rather than welfare of the people, it signals the erosion of democracy and a disguised aristocracy in operation. The State needs to reclaim its role as a Government of the People rather than a Government of the Corporation. Therefore, on the economic front, the government needs to follow a more ‘socialist’ approach taking into account Article 38 and 39 of the Constitution and introduce ‘Wealth Tax’ taxing large corporation on the basis of their wealth.

[3] Duncan Green, The world’s top 100 economies: 31 countries; 69 corporations, The World Bank, (Sept. 20, 2018), Source Link.

[4] M.C Mehta v. Union of India AIR 1987 SC 1086.

[5] Standard Chartered Bank v. Directorate of Enforcement 2005 SCC (Cri) 961.

6. Iridium India Telecom Ltd. v. Motorola Inc&ors (2011) 1 SCC 74.

ISBN: 978-93-5321-910-9 | Copyrights with Jus Dicere & Co.