In the case of Prathvi Raj Chauhan v. Union of India & ors, the Supreme Court of India upheld the constitutional validity of The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2018 and Section 18A. The case revolved around the troubled history of the treatment of ind

Section 18A of the SC/ST Act, 1989 is constitutionally valid.

Section 438 CrPC is not violative of Article 21 of the Constitution.

Citation: Writ Petition (C) No. 1015 of 2018

Date of Judgement: 10 February, 2020

Authors: Justice Arun Mishra (Majority Opinion), Justice S. Ravindra Bhat (Concurrent Opinion)

Bench: Justice Arun Mishra, Justice Vineet Saran, Justice S. Ravindra Bhat

BACKGROUND FACTS

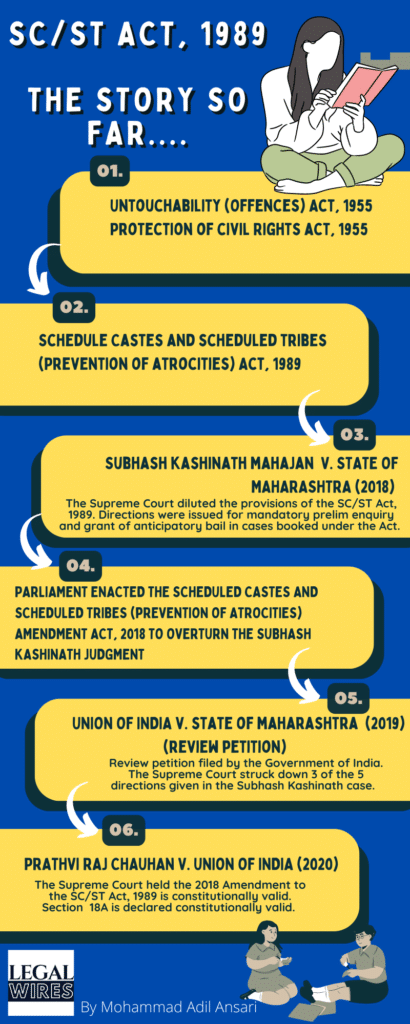

The Indian society has a troubled history with respect to the treatment of individuals belonging to the lower caste. For hundreds of years, they have been subjected to cruelty, torture, exploitation and all forms of gruesome persecution. Their status and plight were not lost upon the makers of the Constitution. Several provisions were incorporated in the Indian Constitution to improve their social position. Concepts such as affirmative action strategy as well as reservation policy were introduced, and untouchability of all forms was explicitly prohibited. But untouchability and such related practices could not be possibility eradicated from a society deeply entrenched with the caste system. Therefore, its derogation required the force of law and punitive sanction. Post-independence, the first attempt by Parliament to achieve such end was through the enactment of the Untouchability (Offences) Act, 1955. The Act introduced a presumption that where any of the enlisted forbidden practices was committed in relation to a member of a Scheduled Caste, the Court shall presume that such act was committed on the ground of “Untouchability”, unless the contrary was proved. The burden of proof was upon the accused to prove his innocence. The same year the Protection of Civil Rights Act, 1955 was enacted which prescribed “punishment for the preaching and practice of – “Untouchability” for the enforcement of any disability arising therefrom”. In short, the Indian state outlawed any social practices and disabilities associated with untouchability and declared them as subject matters of punishment. But the legislation (in spite of the 1976 amendments introduced into its framework) failed to achieve any significant effect and such practises continued to have wide prevalence. In such a scenario, the Parliament brought in the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989 (hereafter referred to as “the SC/ST Act”). The 1995 Rules under the Act were framed, which:

- Sought prevention of the commission of atrocities against members of Schedules Castes and Tribes

- Establishment of special courts for the trial of such offences

- Relief and rehabilitation of the victims of such offences and for matters connected therewith or incidental thereto.

The Statement of Objects and Reasons of the Act, marked an observation that despite various measures to improve the socio-economic conditions of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, their position within Indian society remained vulnerable. They suffer a handicap of a number of civil rights and are subjected to brutal violence, indignities, humiliation and harassment, both at social and institutional level. These atrocities were committed against them for various historical, social and economic reasons. The Act, thus laid down the contours of the definition of ‘atrocity’ so as to encapsulate the multiple ways through which members of scheduled castes and scheduled tribes have been for centuries humiliated, brutally oppressed, degraded, denied their economic and social rights and relegated to perform the most menial jobs.

One prominent feature of the Act was Section 18 which read: “Nothing in section 438 of the Code shall apply in relation to any case involving the arrest of any person on an accusation of having committed an offence under this Act.” The Section denied anticipatory bail in cases which were booked under the Act.

But in the 2018, a division bench decision of the Supreme Court, in the case of Subhash Kashinath Mahajan v. State of Maharashtra & Ors[1], toned down the application of the provision and held that the exclusion of anticipatory bail provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure did not constitute an absolute bar for the grant of bail. If the circumstances of the case make it discernable to the court that the allegations about atrocities or violation of the provisions of the Act are false, bail can be granted. Moreover, It was also held, that the arrest of the public servants can be made only after an approval by the appointing authority and in other cases, after approval by the Senior Superintendent of Police. The Supreme Court also gave the direction that that cases under the Act could be registered only after a preliminary enquiry into the complaint.

This verdict, delivered on 20th of March, 2018 caused massive uproar in the Dalit community throughout the country. A Bharat Bandh Andolan throughout the nation was called for on 2nd of April, 2018. Various Dalit groups organised an all-India strike against the Supreme Court’s judgement barring the arrest of public servants under the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Prevention of Atrocities Act, 1989 before a preliminary inquiry is conducted, apparently to curb the alleged misuse of the law. The protests were widespread and forceful, often descending into violence at many places and provoking violent reactions from upper caste groups. Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh saw deaths while Punjab requested the Union Home Ministry for paramilitary forces to control the situation.[2] Twenty-two people were reportedly killed in the protests.

According to Bharti the head of National Confederation of Dalit Organisations (NACDOR), the judicial system in this country had failed Dalits and Adivasis time and again. Right from 1990s, the higher judiciary has been deciding and affecting the life and livelihoods of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes without hearing their perspective and without consulting even National Commission for Scheduled Castes and the Commission for Scheduled Tribes. It was alleged that the two-member bench of the Supreme Court on March 20 passed an order that directly affected the lives of 30 crore people without hearing the views of the SCs and STs on the subject.[3]

P.S. Krishnan, the draftsman of the 1989 Act, former Secretary to Union ministry of welfare, and a member of the National Monitoring Committee for Education of Scheduled Castes, Scheduled Tribes and Persons with Disabilities, expressed his distress over the Supreme Court’s judgment on March 20 diluting the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) (POA) Act 1989 and the POA Amendment Act, 2015. Krishnan recalls that the 1989 Act was enacted by the then Rajiv Gandhi government in view of the rampant perpetration of atrocities on SC/STs. The Act was operationalised by the succeeding V.P. Singh government. He apprehends that dilution of Section 18 of the Act by conditions such as those directed in the judgment will encourage such police and other officers who suffer from widespread caste bias, and demoralise and scare the already weak and vulnerable SCs and STs. [4]

The verdict received massive criticism from all corners of the country. The political class also unilaterally condemned the verdict alleging it to dilute the special legislation.

Consequentially, the Union of India, moved for a review of the decision. In the review proceedings, the decision was recalled and all its directions (with the exception of Direction number (ii)[5] which relaxed the prohibition on the grant of anticipatory bail in complaints filed under the SC/ST Act) were overruled by the 3 judge bench in the case of Union of India v. State of Maharastra.[6]

In the meanwhile, Parliament enacted the amendment ‘The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2018 (by Act No. 27 of 2019)’ to undo the effect of the Subhash Kashinath Mahajan decision. The Amendment Act introduced Section 18A to the SC/ST Act which reads:

“Section 18A. No enquiry or approval required.- (1) For the purposes of this Act,–

a) preliminary enquiry shall not be required for registration of a First Information Report against any person; or

(b) the investigating officer shall not require approval for the arrest, if necessary, of any person, against whom an accusation of having committed an offence under this Act has been made and no procedure other than that provided under this Act or the Code shall apply.

(2) The provisions of section 438 of the Code shall not apply to a case under this Act, notwithstanding any judgment or order or direction of any Court.”

The petitioner challenged the constitutional validity of newly introduced, Section 18A.

JUDGMENT

The bench upheld the constitutional validity of The Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Act, 2018 and Section 18A. Relying on the judgment of State of M.P. & Anr. v. Ram Kishna Balothia & Anr.[7], Justice Arun Misra speaking for the majority laid down that Section 18A concerns a special genus of offences, mentioned in Section 3 of the Act, which are directed against a special class, namely SC/ST groups. Hence it is not violative of Article 14 of the Constitution. Moreover Section 438 CrPC, is not an integral part of Article 21 hence cannot be claimed as a matter of Fundamental right. It is only a statutory right introduced after the recommendations of 41st Law Commission Report. The statutory right can be made subject to certain restrictions by the legislature, thus its non-application to complaints falling within the ambit of SC/ST Act, 1989 is permissible within the legislative framework.

However with respect to false complaints, the Court held that if the complaint does not make out a prima facie case for applicability of the provisions of the Act of 1989, the bar created by section 18 and 18A (i) shall not apply and the court can exercise its power under Section 482 Cr.PC for quashing the cases to prevent misuse of provisions on settled parameters, as already observed while deciding the review petitions

In his concurrent opinion, Justice Bhat reinforced upon the idea of fraternity citing the quotes from Saint Kabir, Guru Nanak, Guru Granth Saheb as well as Dr. Ambedkar. He pointed out how fraternity along with equality and liberty forms a trinity of preambular vision of the Constitution. He said, “The articulation of fraternity as a constitutional value, has lamentably been largely undeveloped. In my opinion, all the three – Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, are intimately linked. The right to equality, sans liberty or fraternity, would be chimerical…..liberty without equality or fraternity, can well result in the perpetuation of existing inequalities and worse, result in license to indulge in society’s basest practices. It is fraternity, poignantly embedded through the provisions of Part III, which assures true equality.”[8]

The Act has been implemented in the backdrop of a segmented widely divided society and it aims to give effect the idea of Fraternity (Bandhutva) enshrined in the Constitution. Thus, it cannot be held violative of fundamental rights rather reinforce them in the spirit of fraternity.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

1. Can a law be struck down on the ground that it can be used for false accusations to implicate innocents?

It is important to keep oneself reminded that while sometimes (perhaps mostly in urban areas) false accusations are made, those are not necessarily reflective of the prevailing and wide spread social prejudices against members of these oppressed classes.

All these considerations far outweigh the petitioners’ concern that innocent individuals would be subjected to what are described as arbitrary processes of investigation and legal proceedings, without adequate safeguards. The right to a trial with all attendant safeguards are available to those accused of committing offences under the Act; they remain unchanged by the enactment of the amendment.

2. Section 18A of the Act refuses anticipatory bail in all cases wherein a complaint has been booked under the Act. Is it legal and if not, then what is the alternate remedy available to the accused person?

Yes.

In cases where no prima facie materials exist warranting arrest in a complaint, the court has the inherent power to direct a pre-arrest bail.

However, the power is to be used sparingly and under exceptional circumstances. It cannot be used in a liberal or regular manner for that would defeat the intention of the Parliament with respect to the Act. The point for the consideration for Courts in such cases shall be that “while considering any application seeking pre-arrest bail, the High Court has to balance the two interests: i.e. that the power is not so used as to convert the jurisdiction into that under Section 438 of the Criminal Procedure Code, but that it is used sparingly and such orders made in very exceptional cases where no prima facie offence is made out as shown in the FIR, and further also that if such orders are not made in those classes of cases, the result would inevitably be a miscarriage of justice or abuse of process of law.

3. Section 18A (which restores the previously, Section 18) of the SC/ST Act bars the application of Section 438 CrPC in cases booked under the SC/ST Act. Does a bar on Section 438 CrPC to seek anticipatory bail violate Article 14 of the Constitution?

No.

The offences under the SC/ST Act, 1989 constitute a special class which exclusively deals the practise of untouchability prohibited under Article 17 of the Indian Constitution. Therefore, its stringent provisions are protected under Article 14 of the Constitution rather than in violation of it.

The court reiterated the position established in the case of State of M.P. & Anr. v. Ram Kishna Balothia & Anr.[9] that : “It is undoubtedly true that Section 438 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which is available to an accused in respect of offences under the Penal Code, is not available in respect of offences under the said Act. But can this be considered as violative of Article 14? The offences enumerated under the said Act fall into a separate and special class. Article 17 of the Constitution expressly deals with abolition of ‘untouchability’ and forbids its practice in any form. It also provides that enforcement of any disability arising out of ‘untouchability’ shall be an offence punishable in accordance with law. The offences, therefore, which are enumerated under Section 3(1), arise out of the practice of ‘untouchability.’ It is in this context that certain special provisions have been made in the said Act, including the impugned provision under Section 18, which is before us. The exclusion of Section 438 of the Code of Criminal Procedure in connection with offences under the said Act has to be viewed in the context of the prevailing social conditions which give rise to such offences, and the apprehension that perpetrators of such atrocities are likely to threaten and intimidate their victims and prevent or obstruct them in the prosecution of these offenders, if the offenders are allowed to avail of anticipatory bail. In this connection, we may refer to the Statement of Objects and Reasons accompanying the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Bill, 1989, when it was introduced in Parliament. It sets out the circumstances surrounding the enactment of the said Act and points to the evil which the statute sought to remedy. In the Statement of Objects and Reasons, it is stated:

“Despite various measures to improve the socio-economic conditions of the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes, they remain vulnerable. They are denied number of civil rights. They are subjected to various offences, indignities, humiliations, and harassment. They have, in several brutal incidents, been deprived of their life and property. Serious crimes are committed against them for various historical, social, and economic reasons.”

4. Does a bar on Section 438 CrPC violate Article 21 of the Constitution?

No.

Section 438 CrPC is not an extension of the rights granted under Article 21. It’s a statutory discretionary power in the hands of Sessions Court or High Court, which can be utilized only in exceptional cases in light of extenuating circumstances. It cannot be read to imply as a matter of right of an individual.

The Court quoted the rationale given in State of M.P. & Anr. v. Ram Kishna Balothia & Anr., (1995) 3 SCC 221 to elaborate its position on the matter:

“We find it difficult to accept the contention that Section 438 of the Code of Criminal Procedure is an integral part of Article 21. In the first place, there was no provision similar to Section 438 in the old Criminal Procedure Code. The Law Commission in its 41st Report recommended introduction of a provision for grant of anticipatory bail. It observed: “We agree that this would be a useful advantage. Though we must add that it is in very exceptional cases that such power should be exercised.”

In the light of this recommendation, Section 438 was incorporated, for the first time, in the Criminal Procedure Code of 1973. Looking to the cautious recommendation of the Law Commission, the power to grant anticipatory bail is conferred only on a Court of Session or the High Court. Also, anticipatory bail cannot be granted as a matter of right. It is essentially a statutory right conferred long after the coming into force of the Constitution. It cannot be considered as an essential ingredient of Article 21 of the Constitution. And its non-application to a certain special category of offences cannot be considered as violative of Article 21.”

[1] (2018) 6 SCC 454

[2]Daniyal Shoaib, The WhatsApp wires: How Dalits organised the Bharat Bandh without a central leadership, https://scroll.in/article/874714/the-whatsapp-wires-how-dalits-organised-the-bharat-bandh-without-a-central-leadership (accessed on 23rd May, 2019)

[3] Munshi Suhas, Man Behind April 2 Bharat Bandh’ Has Deadline for PM Modi and Ultimatum for Mayawati, https://www.news18.com/news/india/man-behind-bharat-bandh-has-a-deadline-for-modi-ultimatum-for-mayawati-1716863.html ( accessed on 23rd May, 2019)

[4] The Wire Staff, Dilution of SC/ST Atrocities Act Will Have a Crippling Effect on Social Justice, https://thewire.in/law/dilution-of-sc-st-atrocities-act-will-have-a-crippling-effect-on-social-justice (accessed on 24th May, 2019)

[5] In Dr. Subhash Kashinath Mahajan v. The State of Maharashtra & Anr., (2018) 6 SCC 454, following directions were issued:

“83. Our conclusions are as follows:

- Proceedings in the present case are clear abuse of process of court and are quashed.

- There is no absolute bar against grant of anticipatory bail in cases under the Atrocities Act if no prima facie case is made out or where on judicial scrutiny the complaint is found to be prima facie mala fide. We approve the view taken and approach of the Gujarat High Court in Pankaj D. Suthar (supra) and Dr. N.T. Desai (supra) and clarify the judgments of this Court in Balothia (supra) and Manju Devi (supra);

- In view of acknowledged abuse of law of arrest in cases under the Atrocities Act, arrest of a public servant can only be after approval of the appointing authority and of a non-public servant after approval by the S.S.P. which may be granted in appropriate cases if considered necessary for reasons recorded. Such reasons must be scrutinised by the Magistrate for permitting further detention.

- (iv) To avoid false implication of an innocent, a preliminary enquiry may be conducted by the DSP concerned to find out whether the allegations make out a case under the Atrocities Act and that the allegations are not frivolous or motivated.

- Any violation of directions (iii) and (iv) will be actionable by way of disciplinary action as well as contempt.

The above directions are prospective.”

However, directions no.(s) iii, iv and v were recalled by the Supreme Court in a review petition Union of India v. State of Maharashtra and others, filed by the Government of India which was decided on 1st October 2019.

[6] REVIEW PETITION (CRIMINAL) NO.275 OF 2018

[7] (1995) 3 SCC 221

[8] Para 4

[9] (1995) 3 SCC 221