Aug 21, 2020 15:44 UTC

| Updated:

Aug 21, 2020 at 15:46 UTC

Who are Refugees?

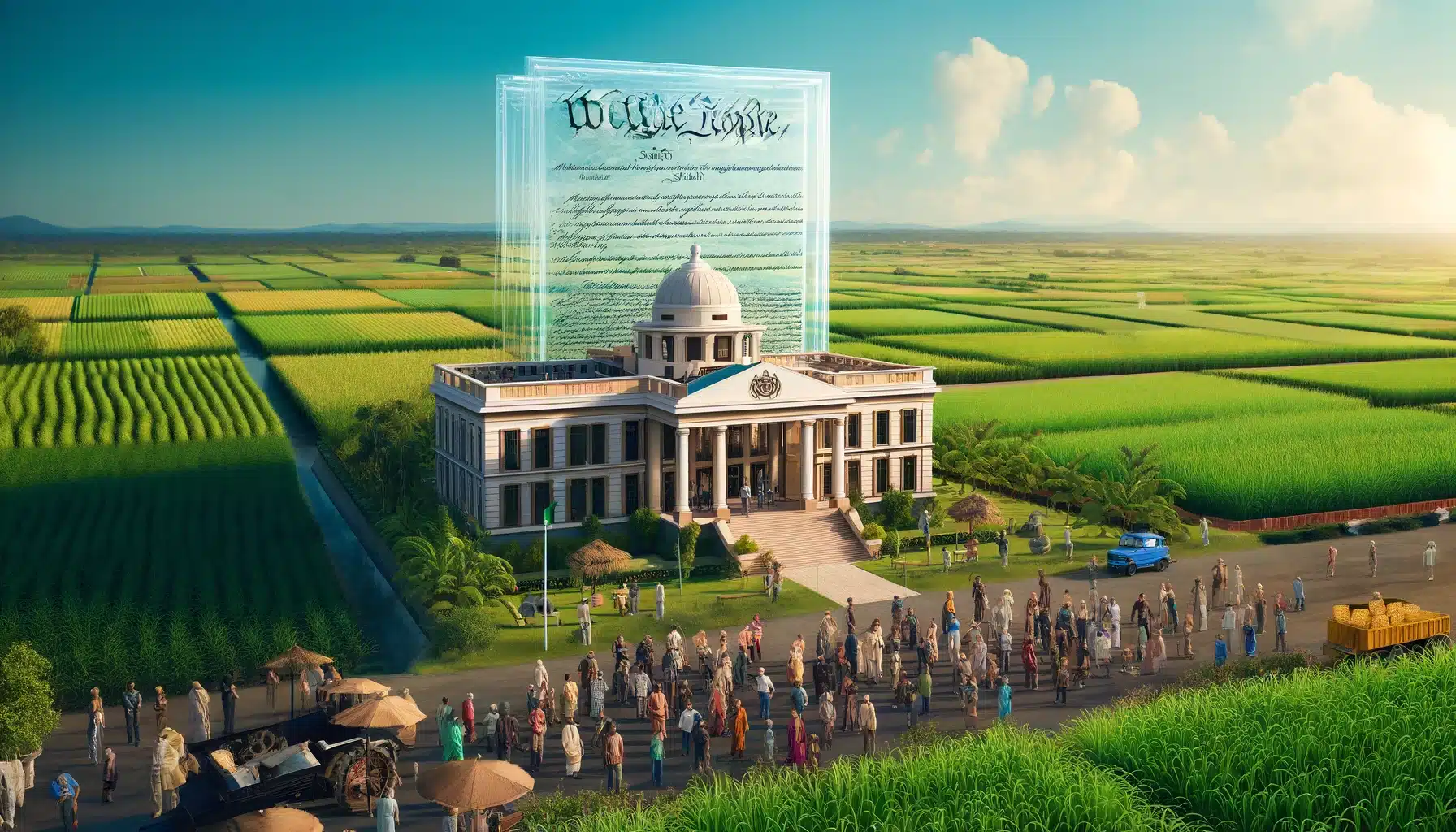

India has had an age-old custom of rendering humanitarian guard to refugees and asylum pursuers[1]. It has trailed a very generous refugee strategy. Nevertheless, the absence of a refugee specific legislation is often accredited to India’s volatile situation in South Asian politics and therefore the menace of terrorism confronted by it. Even in such an absence of such laws, India has addressed the requirements of refugees who have fled from their home country into its territory.

India hosted around 420,400 refugees, together with some 110,000 from Tibet who fled since China’s 1951 annexation. Additional 102,300, typically Tamil Sri Lankans, fleeing fighting between the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and the Sri Lankan armed forces. There were about 36,000 Buddhist cultural Chakmas and Hajongs from modern Bangladesh who escaped to Arunachal Pradesh subsequently Muslim annexation of their terrestrial in 1964.

India has shown discrepancy between accepting refugees from different nations. There were two major refugee flows from Bangladesh. The Chakmas were given inadequate facilities as confirmed by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and repatriated in 1988. Tibetan refugees received much better treatment as compared to other refugee groups. Concerning Sri Lankan Tamil refugees, a politician’s refugee determination process has been practiced and therefore the principle of non-refoulement has been complied with.

The International convention handling the difficulty of refugees is that the 1951 Convention on Status of Refugees and therefore the 1967 Protocol attached thereto. The term ‘refugee’ is defined as –

“a person owing to justifiable dread of being maltreated for motives of race, religion, nationality, membership of a specific group or political opinion, is exterior the nation of his nationality and is unable or, due to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of that protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside a country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, due to such fear, unwilling to return thereto .”

India features a federal foundation and is described as a Union of States. This union is considered as a State in the law of nations. The Union legislature, i.e., the Parliament alone is given the power to deal with the topic of citizenship, naturalization, and aliens. India has not passed a refugee specific legislation that regulates the entry and standing of refugees. It has moved the refugees under radical and secretarial levels. The result is that they are treated under the law applicable to aliens in India, unless a special provision is formed similarly situating with the circumstance of Ugandan refugees (of Indian derivation) when it conceded the Immigrants as of Uganda Order, 1972[2].

India is not a party to the 1951 Convention[3] or the 1967 Protocol[4]. An individual refugee is protected essentially under the Constitution of India since there has been no domestic legislation passed on this topic. But the provisions of those international treaties have now acquired the status of the customary law of nations and are usually considered to have been incorporated into the domestic law to the extent of their consistency with the prevailing municipal laws and also when there’s a void within the municipal laws. Also, Article 51(c) of the Constitution of India advocates fostering respect for the law of nations.

The legal framework in India

In India, refugees are well-thought-out under the domain of the term ‘alien’. The word alien appears within the Constitution of India (Article 22, Para 3 and Entry 17, List I, Schedule 7), in Section 83 of the Indian Civil Procedure Code, and in Section 3(2)(b) of the Indian Citizenship Act, 1955, as well as some other statutes. Enactments governing aliens in India are the Foreigners Act, 1946 under which the Central Government is empowered to manage the entry of aliens into India, their presence and departure therefrom; it defines a ‘foreigner’ to mean ‘a one that isn’t a citizen of India’. The Registration Act, 1939 pacts with the registering of foreigners inflowing, being contemporary in and leaving from India. Also, the Passport Act, 1920, and therefore the Passport Act, 1967 deals with the powers of the government to impose conditions of passport for entry into India and to issue passport and travel documents to regulate departure from citizens of India.

Subsequently, these laws don’t make any discrepancy amongst genuine refugees and supplementary groupings of aliens, however, refugees acceptance is jeopardised by their arrest by the migration establishments and of their trial if they arrive in India without a lawful passport/travel paper. As soon as a refugee is imprisoned by customs, immigration, or law enforcement agency establishments for a charge of any of the wrongdoings under the above-mentioned laws, he’s generally tendered over to the constabularies and a first Information Report is lodged against him. According to the provisions of those statutes, the refugee may face forced deportation at the established seaports, airports, or the entry points at the international border if he is detected without valid travel documents. He can also be detained and interrogated resulting in a pending decision by the executive authorities regarding his plea for refugee/asylum. A refugee also faces the prospects of prosecution for violation of the Registration of Foreigners Act, 1939[5] and Rules made thereunder and if he is found guilty of any offence under this Act he may be punished with imprisonment which may extend to one year or with a fine up to one thousand rupees or with both.

Nevertheless, in numerous cases the courts have occupied a merciful interpretation in the substance of penalty for their prohibited entrance or illegal happenings in India and also, by discharging captives pending the determination of refugee status, staying deportation and allowing them to approach the United Nations High Commissioner of Refugees[6], refugees continue to run the danger of uneasiness, imprisonment and trial for the defilement of the Foreigner’s Act, 1946 and the Foreigners Order,1948. The Indian Supreme Court has also held that the government’s right to deport is absolute:

‘… the facility of the government in India to expel foreigners is absolute and unlimited and there’s no provision within the Constitution fettering this discretion… The chief Government has unrestricted right to expel a foreigner.‘

The question that arises here is whether refugees as a special class of aliens possess any more rights than aliens in general?

Constitutional Framework for Protection of Refugees

The Constitution of India guarantees certain Fundamental Rights to refugees. Namely, right to equality (Article 14), right to life and private liberty (Article 21), right to protection under arbitrary arrest (Article 22), right to guard in respect of conviction of offenses (Article 20), freedom of religion (Article 25), right to approach Supreme Court for enforcement of Fundamental Rights (Article 32), are as much available to non-citizens, including refugees, as they are to citizens.

The constitutional rights protect the human rights of the refugee to live with dignity. The liberal interpretation that Article 21 has received now includes right against solitary confinement, right against custodial violence, right to medical assistance, and shelter.

The Supreme Court has taken recourse to Article 21 of the Constitution within the absence of legislation to manage and justify the stay of refugees in India.

In NHRC v. State of Arunachal Pradesh, the govt of Arunachal Pradesh was asked to perform the duty of safeguarding the life, health, and well-being of Chakmas residing within the State and that their application for citizenship should be forwarded to the authorities concerned and not withheld. In various other cases, it was held that refugees should not be subjected to detention or deportation and that they are entitled to approach the U.N High Commissioner for grant of refugee status.

In P. Nedumaran v. Union of India[7] The need for voluntary nature of repatriation was emphasized where the Court held that the UNHCR, being a world agency, was to ascertain the voluntariness of the refugees and, hence, it was not on the Court to think about whether consent was voluntary.

Similarly, according to B. S. Chimni, the Supreme Court has erred in concluding in Louis de Raedt v Union of India[8] that there’s no provision within the Constitution fettering the and unlimited power of the govt to expel foreigners under the Foreigners Act of 1946.

In real sense, Article 21[9] The Indian Constitution does impose certain constraints: any action of the State which deprives an alien of his or her life and private liberty without a procedure established by law would fall foul of it, and such action would include the refoulement of refugees. Therefore, the author opined that the Court should have proceeded to check the validity of the Foreigners Act as against Article 21.

Incorporating International Law in Domestic Law

International law has accepted and defined refugees as a special class of aliens. Does this acceptance by the law of nations import any legal consequence on the Indian Government within the absence of any legislation on the subject?

Indeed, India has not ratified the 1951 Convention and therefore the 1967 Protocol thereto, however, it acceded to varied Human Rights treaties and conventions that contain provisions relating to the protection of refugees. As a celebration to those treaties, India is under a legal obligation to guard the human rights of refugees by taking appropriate legislative and administrative measures under Article 51(c) and Article 253, and also under an equivalent law, it’s under the requirement to uphold the principle of non-refoulement. India is a member of the Executive Committee of the office of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees which puts a moral, if not a legal obligation, on it to build a constructive partnership with UNHCR by following the provisions of the 1951 Refugee Convention.

Regarding adopting international conventions in domestic laws, in Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan, the Court observed that reliance is often placed in international laws. Therefore, the question that arises is whether or not India can read the 1951 Convention in interpreting the domestic legislation and whether it’s really necessary to ratify these conventions. It is to be noted that merely ratifying the 1951 Convention doesn’t make sure that the asylum seekers won’t be kept out and also Article 42 of the same Convention permits reservations for the rights of refugees which will defeat the purpose of ratifying the Convention.

The solution to treat refugees with dignity in India is to either to ratify the 1951 Convention and incorporate it into domestic law or enact consistent legislation specifically for refugees so that it’s not left to the discretion of the chief and therefore the judiciary to decide their fate.

[1] Source link.

[2] Source link.

[3] Source link.

[4] Source link.

[5] Source link.

[6] (hereinafter referred to as UNHCR)

[7] 1993 (2) ALT 291, 1993 (2) ALT Cri 188

[8] 1991 AIR 1886, 1991 SCR (3) 149

[9] Protection of life and personal liberty No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law