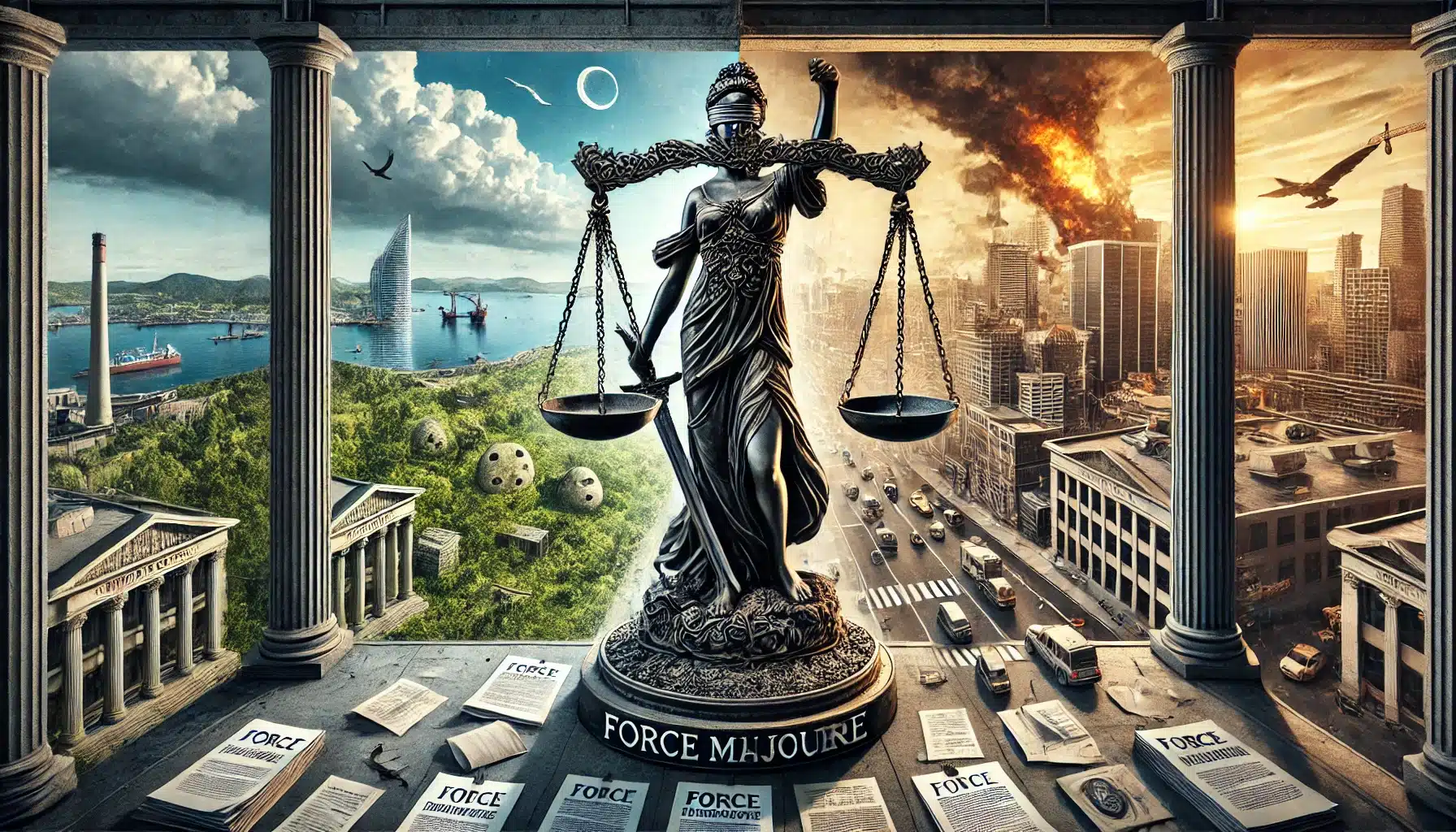

Force majeure is a clause inculcated in contract agreement in order to remove liability for unforeseeable and unavoidable catastrophes interrupting the expected timeline and preventing participants from fulfilling obligations, generally termed as “act of god”

Definition

Ordinary event prevents them from performing: “superior force” or “major force” and is often associated with “acts of God”. Apart from this ‘Force Majeure’ is wider than ‘Vis Major’/ ‘Act of God’ since the former encompasses both natural and artificial unforeseen events whereas the latter contemplates only natural unforeseen events. In fact, ‘Vis Major’ or ‘Act of God’ actually forms a sub-set of ‘Force Majeure’, even Supreme Court has, recognized the difference between ‘Act of God’ or ‘Vis Major’ and ‘Force Majeure’.[1]

Origin and Evolution

The term ‘Force Majeure’ appeared in the common law world in the 1900s and was borrowed from the Napoleonic Code[2], although its origins can be traced back to Roman law which recognized that the principle of sanctity of contract can be tempered by a competing principle ‘clausula rebus sic stantibus’, which means obligations under a contract are binding only as long as matters remain the same as they were at the time of entering into the contract.

Further it is exercised to excuse non-performance of a party and prevent a party from being liable for a breach of contract[3] and sometime also protecting the non-performing party from the consequences of something over which it has no control.[4]

Meaning and understanding

Force majeure is the situation-based doctrine under which unpredicted event may excuse liability for non-performance, provided that the so unexpected event is unforeseeable, uncontrollable in nature, and makes the performance of an obligation impossible thus qualifying as a “force majeure event”, it was majorly in context during covid-19 pandemic. Force majeure events may include natural disasters or man-made constraints (e.g. war, civil unrest).

If we talk of Indian law, then the first decisions to deal with the concept of force majeure was the Madras High court[5], where court referring to Matsoukis v. Priestman and Co[6], adopted the definition given by an eminent Belgian lawyer of force majeure as meaning “causes you cannot prevent and for which you are not responsible”.

There are majorly two provisions in Indian law[7] which are relevant to Force Majeure and Act of God, i.e., Section 32 of the Act, dealing with contingent contracts and inter alia provides that if a contract is based on the happening of a future event and such event becomes impossible, the contract becomes void. And other is Section 56 of the Act which focus on frustration of a contract and provides that a contract becomes void inter aliaif it becomes impossible, by reason of an event which a promisor could not prevent, after the contract is made.

Difference between force majeure and frustration of contract

Under the doctrine of frustration, impossibility of a party to perform its obligations under a contract is linked to occurrence of an event/circumstance subsequent to the execution of a contract and which was not contemplated at the time of execution of the contract, whereas in case of a force majeure, parties typically identify, prior to the execution of a contract, an exhaustive list of events, which would attract the applicability of the force majeure clause.

Frustration of a contract is invoked and applied requires that the entire subject matter or underlying rationale for the contract be destroyed and on the other hand Doctrine of Frustration renders the contract void and consequently all contractual obligations of the parties cease to exist.

When Forced Majeure is invoked, the affected party may be freed from executing contractual responsibilities and rights in exchange for meeting the contract’s requirements. It is valid until the end of the event and does not completely exclude parties from performing. On the other hand doctrine of Frustration, is concerned with the contract’s entire reason or purpose becoming void and unable to be carried out.

This concept also holds that any contractual duties that the parties were supposed to fulfil cease to exist. In more static terms, this concept applies when an occurrence is not foreseen nor specified in the contract, i.e. when the incident was not stated under the Forced Majeure clause. The affected party can invoke this doctrine, but it cannot be invoked if the case is the opposite.

Conclusion

Force majeure clauses can usually be found in various contracts such as power purchase agreements, supply contracts, manufacturing contracts, distribution agreements, project finance agreements, agreements between real estate developers and home buyers, etc., and is important for businesses as it relieves the parties from performing their respective obligations and which are to be undertaken under the contract and consequential liabilities, during the period that force majeure events continue provided that the conditions for clause to become applicable.

[1] Dhanrajamal Gobindram v. Shamji Kalidas & Co, AIR 1961 SC 1285.

[2] Lebeaupin v. Crispin [1920] 2KB 714.

[3] Phillips P.R. Core, Inc. v. Tradax Petroleum Ltd., 782 F.2d 314, 319 (2d Cir. 1985).

[4] Dhanrajamal Gobindram v. Shamji Kalidas & Co., AIR 1961 SC 1285.

[5] Edmund Bendit and Anr v. Edgar Raphael Prudhomme, AIR 1925 MADRAS 626.

[6] [1915] 1 K.B. 681.

[7] Indian Contract Act, 1872.