The SC upheld the UP Madarsa Act, balancing state regulation with minority rights, emphasizing secularism as coexistence, not negation, ensuring quality education without infringing religious freedoms.

Introduction

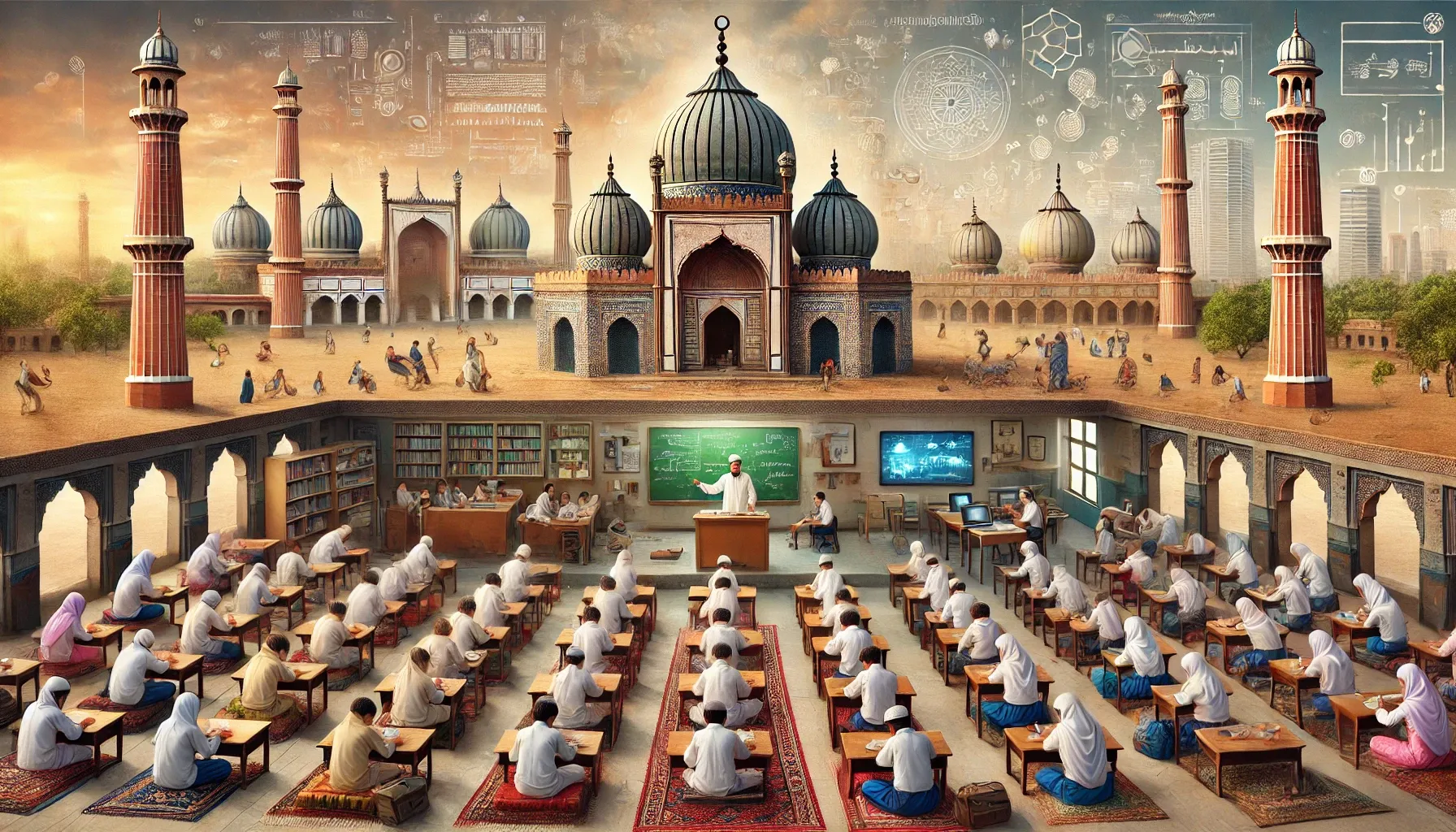

When we think of Madarsas in India, images of traditional religious schools often come to mind, places where students not only learn the Quran but also delve into classical Islamic studies. However, the concept of Madarsa education in India is far more complex, caught in the ever-evolving interplay between constitutional rights, secularism, minority protections, and the state's regulatory powers. One such pivotal case that has captivated legal and political debates in recent months is the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004. At the heart of the controversy lies a simple question: Can the state regulate religious institutions to ensure quality education, or does such regulation violate the very fabric of India’s secular framework?

The Supreme Court in the latest decision in this matter, has not only clarified the legal contours of Madarsa education but has also sparked a national conversation about the balance between constitutional secularism and religious freedoms. This judgment holds deep implications for how India should manage its diverse educational institutions in the future, especially those catering to minority communities. But what does this case truly signify? Let’s take a deeper insight at the Supreme Court’s reasoning and the political, legal, and social dimensions surrounding the issue.

The Case at a Glance: A Clash of Legal Interpretations

The present issue arose from the March 2024 ruling of the Allahabad High Court[1], which ruled that the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act, 2004 was unconstitutional. The Act was criticized by the Allahabad High Court, claiming that it went against the fundamental secularism principle. According to the court, the Act violated secular principles enshrined in the Indian Constitution by aiming to standardize and regulate Madarsa education, infringing upon religious freedoms. Court cited “In view of the foregoing discussion, we hold that the Madarsa Act, 2004, is violative of the principle of Secularism, which is a part of the basic structure of the Constitution of India, violative of article 14, 21 and 21-A of the Constitution of India and violative of section 22 of the University Grants Commission Act, 1956. Accordingly, the Madarsa Act, 2004 is declared unconstitutional. Further, we are not deciding the validity of Section 1(5) of the R.T.E. Act as we have already held the Madras Act to be ultra vires and we are also informed by learned counsel for both the parties that in the State of U.P. Vadik Pathshalas do not exist.”[2]

However, the petitioners including various Madarsa associations contended that the High Court had misinterpreted the original purpose of the Act. They mentioned Commissioner, Hindu Religious Endowments, Madras v. Sri Lakshmindra Thirtha Swamiar[3] argued that the Madarsa Act was not about religious indoctrination, but rather it was a legislative effort to regulate educational standards within Madarsas, providing Muslim children with an education that prepares them for mainstream society. In contrast, opponents of the Act, including the National Commission for Protection of Children’s Rights (NCPCR), argued that such education was inferior and incompatible with the constitutional guarantee of quality education under Article 21A. They feared that religious education would undermine children's ability to engage in a competitive, modern world.

A Reassessment of the Secularism Debate

At the heart of the debate lay the question of secularism: should the state have the power to regulate religious institutions to ensure they meet educational standards? The Supreme Court’s ruling firmly addressed this issue, rejecting the High Court’s premise that the Madarsa Act violated the principle of secularism by regulating religious institutions. The Court’s reasoning was clear: “A statute cannot be struck down for violation of the basic structure of the Constitution. To challenge a statute on the grounds of secularism, it must be shown that the statute violates specific provisions of the Constitution that pertain to secularism.”

In contrast, the Supreme Court ruled that secularism is a broad and somewhat fluid concept, one that cannot be used as a catch-all reason to invalidate laws. The Court emphasized that legislation should only be struck down for violation of fundamental rights under Part III of the Constitution or when it falls outside the legislative competence defined in the Constitution. As Chief Justice Chandrachud noted, “The constitutional validity of a statute cannot be challenged solely on the basis of an alleged violation of the basic structure principle of secularism. The High Court erred in holding that a statute is bound to be struck down if it is violative of the basic structure.”[4] This clarification serves as a significant precedent, underscoring that secularism is a guiding ethos rather than an independent basis for judicial review. By affirming this, the Court placed the Madarsa Act within the ambit of permissible state action.

This judgment is significant not just for its legal implications but for its larger commentary on the role of the state in regulating religious institutions in a secular democracy. The Supreme Court’s decision reaffirmed the state’s obligation to ensure that all educational institutions, religious or otherwise, must meet minimum standards that facilitate children for modern life and education while also protecting their rights to practice their faith.

Understanding the Madarsa Act and the Court’s Approach

To understand the Supreme Court’s ruling, we must first understand the objectives of the Madarsa Act itself. The Act was formulated to regulate the educational standards in Madarsas, ensuring that students not only receive religious instruction but also a formal education that prepares them for societal participation and better development. This dual purpose is crucial in understanding why the Court upheld the statute’s constitutionality.[5]

The Court recognized that Madarsas serve as vital educational institutions for a significant section of the Muslim population not only in Uttar Pradesh but all over the country. These institutions are responsible for imparting both religious and secular education, preparing students to contribute to society in various capacities. The Madarsa Act was viewed as a mechanism to align these institutions with the educational needs of a modern society, ensuring that students have the competencies to engage in the broader world, while not stripping the Madarsas of their religious character.

The Court in paras 70,72,73,74 and other para: stressed that the state’s involvement in regulating Madarsas was within its rights. The state’s responsibility, according to the Court, was not to interfere with religious teachings per se but to ensure that these institutions offered a baseline of educational quality that allowed students to thrive outside the religious sphere. This means that while Madarsas could continue to offer religious education, they were also required to meet certain academic standards, such as teaching subjects like science, math, and language, so that students did not miss out on a holistic education.

This pragmatic approach acknowledged the reality of India’s plural society: educational systems must accommodate diverse needs, and secularism should not be used as a shield to deny children access to education that will allow them to flourish in all spheres of life.

The Court's Narrow Approach to Secularism

One of the most compelling aspects of the judgment is the Court’s careful delineation of what constitutes a violation of secularism under the Indian Constitution. Secularism, as envisaged by the Constitution, is not an absolute barrier to religious activity but rather a principle that mandates the state’s neutrality in religious matters. As long as an educational institution does not engage in actions that directly infringe upon the rights of others or violate constitutional norms, it cannot be deemed unconstitutional merely because it has a religious component.

The Court’s judgment makes it clear that secularism cannot be treated as a blanket concept under which all state interference with religious institutions is automatically invalidated. In fact, the Court argued that religious instructions imparted in Madarsas do not, by themselves, violate the secular nature of the state. It is only when these religious teachings result in discriminatory or unconstitutional practices such as depriving students of their fundamental rights to education that the state has the authority to intervene.

Thus, while the Madarsa Act regulates education in Madarsas, it does so without crossing the line into religious persecution or undue interference with religious practices. The Act, according to the Court, is a legitimate exercise of the state’s power to regulate education and ensure that it meets certain standards.

A pivotal point in the Supreme Court’s ruling was its approach to the doctrine of secularism. The Court clarified that secularism, although fundamental to the Constitution, cannot serve as a blanket justification for striking down laws, particularly when a statute does not violate specific constitutional provisions.

In its decision, the Court further underscored that legislative actions must only be invalidated when they breach fundamental rights or fall outside the legislature's constitutional competence. In other words, while secularism frames the ethos of the Constitution, it does not independently serve as a test for statutory validity. By focusing on the necessity to show specific infringements, the Court established a rigorous threshold for claims that invoke secularism as a basis for striking down laws.

The NCPCR and the Fear of Religious Education as a Substitute

The NCPCR and other intervenors in the case argued that Madarsa education did not meet the standards necessary to equip students for success in the modern world. These critics contended that the focus on religious education within Madarsas left students ill-prepared for the demands of the competitive job market and society. According to this view, religious instruction could not be considered a substitute for mainstream, secular education, which provides students with a well-rounded knowledge base.

However, the Supreme Court rejected this argument, holding that the regulation of Madarsa education by the state was not a means to eliminate religious instruction but to ensure that students received the basic skills necessary to participate in society. The Court emphasized that Madarsa education could and should serve the dual purpose of promoting both religious and secular learning. It is this balanced approach, the Court suggested, that will allow students to maintain their religious identity while also securing the educational foundation required for a successful future.

Article 21A, Right to Education, and Minority Rights

The Court addressed the delicate intersection of Article 21A (Right to Education) and Article 30 (rights of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions). The Allahabad High Court had found that Madarsa education, focusing on religious teachings, could not fully satisfy the constitutional promise of quality education. However, the Supreme Court rejected this line of reasoning, explaining that Article 21A’s Right to Education does not necessarily override minority rights.[6]

The Court observed, “The Right to Education Act does not apply to minority educational institutions.” The judgment emphasized that the right of religious minorities to establish and administer their educational institutions of choice includes a freedom to impart religious instruction, provided that institutions meet certain academic standards. This balance, the Court argued, allows Madarsas to continue their religious mission while ensuring that students receive adequate education.

The Madarsa Act and Its Implications for Minority Education

In addition to its legal reasoning, the Court’s judgment also addressed the political and social implications of the Madarsa Act. The petitioners argued that the state had the right to regulate Madarsas to ensure that students received a well-rounded education. However, critics raised concerns about the potential for state overreach, especially in minority institutions.

The Court’s ruling made it clear that while Madarsas had the right to impart religious education, they were still required to meet national educational standards. In this sense, the Court positioned the Madarsa Act as a regulatory framework that ensures the quality of education in these institutions, while simultaneously preserving their religious character. This judgment thus emphasizes the importance of protecting the rights of minority communities to establish and administer their own educational institutions, while ensuring that those institutions provide education that is compatible with India’s national educational objectives.

Key Takeaways: A Framework for Religious Institutions and Education

The Supreme Court’s decision has several implications for the future of religious education in India:

- Educational Quality within Religious Institutions: The judgment underscores those religious institutions, including Madarsas, must meet secular educational standards if they wish to operate under state recognition.

- Recognition of Minority Rights under Article 30: By affirming the right of Madarsas to provide religious education, the Court reinforced the protections offered to religious minorities, noting that “the right of religious minorities to establish and administer educational institutions includes the freedom to impart religious education, provided certain academic standards are met.”[7]

- Limits of Secularism in Judicial Review: The Court’s approach to secularism in this case sets an important benchmark, suggesting that secularism alone cannot be grounds for nullifying a law unless the law infringes on specific fundamental rights. This approach reaffirms secularism’s role as a guiding principle, rather than a standalone basis for invalidating legislation.

- Clear Legislative Boundaries between State and Union Jurisdiction: By clarifying the scope of the state’s authority over primary and secondary education and the Union’s control over higher education, the Court has reinforced the legislative boundaries that protect India’s federal structure. This judgment may serve as a reference in future cases where state and Union powers overlap.

Conclusion: The Fine Line Between Secularism and Religious Freedom

The Supreme Court’s verdict on the Uttar Pradesh Board of Madarsa Education Act ultimately reflects a nuanced balance between respecting India’s secular ethos and safeguarding the rights of religious minorities to educate their communities. Chief Justice Chandrachud summed up this balance succinctly: “Secularism does not entail negation of religious identities; it ensures that they coexist within a constitutional framework where individual rights and state obligations are balanced.”

In affirming the validity of the Madarsa Act, the Supreme Court set a new benchmark for how religious institutions are regulated in India. The judgment is offering a sort of roadmap for balancing educational quality with religious autonomy, ensuring that institutions like Madarsas can continue to fulfill both religious and secular educational roles.

As India’s legal landscape evolves, this decision will likely influence how courts interpret the rights of religious institutions, paving the way for a more nuanced understanding of secularism and minority protections in the context of education.

[1] Anshuman Singh Rathore v. Union Of India, 2024: AHC-LKO:25324-DB

[2] Id. at para 99.

[3] 1954 SCR 1005.

[4] Paragraph 54 of (C) No.8541 of 2024.

[5] Joseph Shine v. Union of India, (2019) 3 SCC 39.

[6] Supra note at 45.

[7] Supra note at Paragraph no. 104, C.