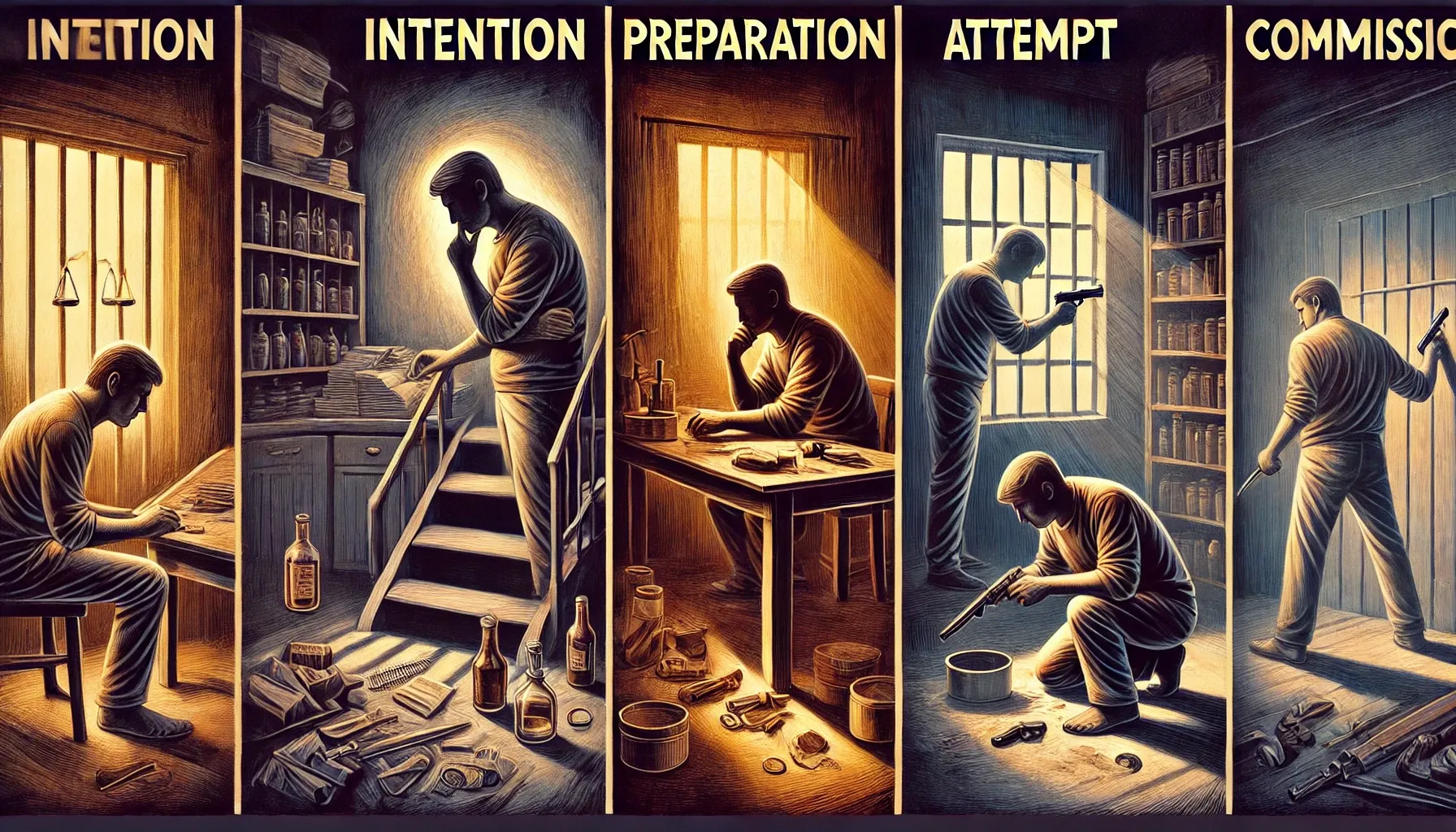

The stages of crime—intention, preparation, attempt, and commission—help determine criminal liability under Indian law, assessing the progression from thought to action for appropriate legal consequences.

Introduction

Crime is a complex phenomenon with multiple stages, each with its own unique characteristics and legal repercussions. In the Indian legal system, comprehending the various stages of crime is critical in evaluating an accused person's guilt or innocence and the necessary legal action to be taken against them, as these stages are regarded critical in identifying an accused person's responsibility and the proper legal penalties for their actions. Understanding the various stages of crime in the IPC helps in examining the accused's mens rea (mental state) and actus reus (physical act), both of which are critical aspects in determining criminal responsibility. The stages of crime give a framework for assessing the accused's responsibility and determining the proper charges and penalties. The intention and preparation stages include mental aspects such as intent and planning, which can be proven through circumstantial evidence, witness testimony, or other relevant evidence. It is essential to note that, in some situations; an accused individual may be charged and convicted under multiple stages under the IPC, now replaced by the BNS. For example, if a person intends to commit murder, prepares by obtaining a weapon, attempts to shoot the victim but misses, and then successfully shoots and kills the victim, they may be charged and convicted of intent, preparation, attempt, and commission of murder, each with its own set of legal implications.

Stages of Crime under Criminal Law

According to the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita Act (BNS) and the Indian Penal Code (IPC), there is a development from the intention to the actual commission of the crime.

The four stages of crime under the criminal law are:

- Intention

- Preparation

- Attempt

- Commission

1. Intention

The fundamental ingredients of a crime are 'mens rea' and 'actus reus', with the former being the desire to commit a crime and the latter being the act carried out in furtherance of that intention. A person's criminal responsibility will be determined only if he or she had malicious intent. The intent behind actions is suggested by the direction toward specific outcomes after evaluating the motive. Since a person's intentions are difficult to determine, mere intention alone does not constitute a crime. As the famous saying goes, "the devil himself knows not a man's intention." Because it is difficult to predict a man's intentions, criminal responsibility cannot be determined at this time.

Mens rea literally means "guilty mind." This basically suggests that the perpetrator is aware of his or her acts and understands that carrying them out will result in a crime. To put it simply, the individual committing a crime should have bad intentions.

Actus reus is an act or omission on the part of a person that results in a crime and requires physical activity. It is critical to understand that not only an act, but also an omission, can constitute a crime.

Illustration

For example, if a person desires to steal a valuable item from a store and plans to do so by entering the business after hours and breaking the lock, the intention to steal is created in the person's mind long before they perform any physical action.

2. Preparation

The preparation stage follows the intention stage and entails taking steps towards carrying out the intended offenses. During this stage, the accused person makes arrangements, gathers resources, and plans the details of the crime, but has not taken any tangible actions toward its execution. The general norm of the law states that the preparation of a crime is not punishable. The reason for the usual rule is that it is nearly impossible to prove that the accused planned to commit the crime. The locus poenitentiae test is used in some cases when determining guilt at the preparation stage. This test allows a person to withdraw from his act before committing the intended crime. The test is further discussed in the following sections.

The Hon'ble Supreme Court ruled in State of Madhya Pradesh v. Narayan Singh[1] that there are four steps involved in committing an offense: intention, preparation, attempt, and commission. Culpability would be applied to the final two stages of these offenses, but not to the first two. In this instance, the responders attempted to export fertilizers from Madhya Pradesh to Maharashtra without an authorization. Therefore, rather than being merely preparation, the act was regarded as an attempt at the offense.

When is preparation punishable:

- Preparation for War Against the Government of India – Section 122 IPC

- Counterfeiting coins - Sections 233, 234, and 235 IPC.

- Manipulation of coin weight - Sections 244, 246, and 247 IPC

- Counterfeiting Government Stamps - Section 255 IPC

- Preparation to commit Dacoity-Sections 399 IPC

- Possession of falsified documents- Section 474 IPC

Illustration

Continuing with the previous example, the individual preparing to steal from the business may begin gathering tools or instruments, such as lock-picking tools or a crowbar, to break the lock. They may also examine the store's layout, determine the optimum moment to perform the theft, and plot their escape route. Certain acts during the preparation stage may be punished by law, depending on the nature of the offenses and the specific provisions of the applicable laws.

3. Attempt

There is a fine line between preparing for a crime and attempting to do it. It may be described as an action taken in furtherance of a person's desire and preparedness to commit a crime. Thus, an attempt to commit a crime is commonly referred to as a "preliminary crime". An attempt to commit a crime is penalized by the Code. It has been included in various laws for specific crimes. Section 511 of the Code, on the other hand, applies where there is no punishment for attempting to commit a specific crime.

When examining the stage of attempt in Madan Lal v. State of Rajasthan[2], the court determined that it is "the stage beyond preparation and it precedes the actual commission of the offence." An attempt to commit a crime includes actions that exceed mere preparation and show a clear intent and resolve to commit a specific crime. It is not limited to the penultimate act towards the execution of an offense. It includes all acts or a sequence of acts that may come before the final act towards the execution of the offense; it need not be an act that only comes before the last act on which the offense itself is committed.

The appellant in Abhayanand Mishra v. State of Bihar[3] was a student taking the Patna University entrance exam for the M.A. in English program. The appellant stated on his application that he was a graduate and that, following graduation, he was teaching in a few schools. But it wasn't until they sent his exam entrance card that the university discovered the information was fake. The appellant argued that it was only preparation to commit fraud and not an effort in the appeal before the Hon'ble Supreme Court. The Court dismissed the argument, ruling that the appellant's submission of the fake information amounted to preparation for fraud and that the sending of the forged documents amounted to an effort. The court reaffirmed that an attempt might refer to any action that advances the preparation, not just the penultimate act.

Illustration

In the preceding scenario, the person intending to steal from the business may visit the store after hours, break the lock with the tools obtained during the preparation step, and enter the store with the purpose to steal. However, if they are apprehended by security or leave the business without stealing anything, it will be deemed an attempt to commit theft.

4. Commission

The commission stage is the ultimate stage of a crime, in which the accused individual successfully completes the offense by executing all of the necessary activities to carry out the intended crime. It is the point at which the accused's mens rea (mental state) and actus reus (physical act) combine, culminating in the commission of the offence. The commission of a crime is penalized under the relevant provisions of the IPC which is replaced by Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, depending on the nature of the offence.

Illustration

In the preceding example, if the individual attempting to steal from the store successfully breaches the lock, enters the store, and steals a valuable item, it is termed stealing.

Post Commission Actions

Certain post-commission actions, such concealing the stolen items, getting rid of the evidence, or trying to flee the scene, may be taken by the accused after a crime has been committed. Depending on the individual legal restrictions and the nature of the offenses, these actions may potentially result in legal repercussions.

Depending on the circumstances, post-commission conduct may be punished under the applicable IPC provisions or other laws.

Illustration

Referring back to the earlier example, the thief may face charges of concealing or disposing of stolen property, both of which are punishable under the applicable IPC (now BNS) provisions, if they conceal the stolen item in their home or sell it to another individual.

Distinction between Preparation and an Attempt

One important distinction is between preparing a crime and really attempting to conduct one. It can establish a person's criminal responsibility. The primary distinction between the two is whether the victim is impacted by the act that has already been completed throughout the course of the crime. It is regarded as an attempt if it has an effect; if not, it is regarded as merely preparation. Using a variety of standards, which will be covered below, the courts have tried to distinguish between the two in a number of cases. The various tests are:

- Proximity rule: According to this rule, if an accused person executes a string of actions in support of his criminal intent, his liability will be determined by how close the Act is completed.

- Locus poenitentiae: According to this rule, a person's refusal to participate in the actual conduct of a crime is equivalent to merely preparing it. After analyzing that a person has a reasonable chance to abstain from committing the crime, the doctrine was developed.

- Equivocality Test: According to this test, an action taken by an individual that establishes beyond a reasonable doubt the likelihood of committing a crime qualifies as an attempt to commit the crime rather than merely preparation.

While distinguishing between an attempt to commit an offense and its preparation, the Calcutta High Court said in Asgarali Pradhania v. Emperor[4] that not all of the accused's actions may be considered attempts to commit the offense. The case's facts included the allegation that he attempted to induce his ex-wife to miscarry. According to the Court, the accused will not be held accountable for attempting to induce miscarriage if, instead of administering a medicine that will cause one, he administers a harmless chemical. On the other hand, the opposite will occur if the accused's failure was brought on by someone else.

Stages at which Liability of Offence Commences

The above discussion explains how the four stages of crime determine an accused's criminal responsibility. Undisputedly, at the level of success, a person's criminal liability will develop. Nonetheless, the preceding discussion demonstrates how liability might begin even at the stage of effort, and in some situations, at the stage of planning. Typically, in such cases, the crime committed is severe and poses a danger to society. As a result, the primary goal of determining culpability at such stages is to produce a deterrent impact in the minds of individuals, preventing them from committing such grave acts.

Conclusion

For many years, the judiciary has defined and adopted the four stages of a crime. According to the Bhartiya Nyaya Sanhita Act (BNS) and the Indian Penal Code (IPC), there is a development from the intention to the actual committing of the crime. The four primary stages—intention, preparation, attempt, and commission—are acknowledged by both codes. The classification of these stages is required in order to determine culpability for a crime at each level. Generally, culpability arises during both the attempt and the actual performance of the crime, as courts cannot ignore the legal maxim of locus poenitentiae. The most common issue before the courts is distinguishing between preparation and attempted criminal activity. Attempts to differentiate between the preparation of a crime and its attempt have been attempted in a number of cases decided by the courts. According to the courts, an attempt should not be regarded as the penultimate act of a crime. Instead, a sequence of actions will be considered an effort to commit the crime, and each case's particular facts and circumstances will determine how preparation differs from attempt. In conclusion, the rich body of jurisprudence under the IPC will be a crucial point of reference for the practical application of the BNS, guaranteeing continuity and clarity in the Indian criminal justice system, even though both the IPC and the BNS offer a structured approach to criminal liability through defined stages.

[1] 1989 AIR 1789.

[2] 1987 CRILJ 257.

[3] 1961 AIR 1698.

[4] AIR 1933 CAL 893.