The Karnataka High Court issued a Bail order dated 19th May, 2020 wherein, it issued some controversial anti-migrant observations. Such observations were unsubstantiated, and seemingly inspired from the fake anti-migrant sentiment propaganda, widespread on social media. The case marks one of the fir

THE KARNATAKA HIGH COURT BAIL CASE

What is Persecution?

Isn’t it Prejudice driven by a chariot of Institutional Violence.

Isn’t it the State which owns the monopoly over violence and its means.

If such are the philosophical realms well established in legal jurisprudence, don’t they cast a duty upon the State institutions to forsake planting such seeds that could weed their entire governance system into becoming agencies of persecution?

If the institutions allow prejudices to dictate their administrative functions and decision, what remains of the democratic way of life and ‘Rule of Law’? Such a responsibility gains paramount importance when the institutions concerned are Judicial; which happen to be ‘the arbiters between the Government and the Governed’.

The Courts are supposed to uphold the ‘Rule of Law’: which presupposes that no man is above the realm of the established law of the land. The Judiciary, being the upholder of this doctrine, cannot be isolated from its application. Therefore, the Judges, sitting on the pulpit of such sacred institutions must be wary of falling into the temptations of primitive human qualities of bias.

The infamous bail order recently passed by the Karnataka High Court in the Babul Khan v. State of Karnataka (CRL.P. No. 6578/2019) unfortunately, happens to falter on such a touchstone when it made observations in para 14:

“Before answering the above points it is just and necessary to bear in mind that, once the appropriate Governments or Union Territories or any other authority is entrusted with the task of identifying, detecting and deporting the illegal migrants, it is their duty to deport them to their respective nation as expeditiously as possible. The Courts should also bear in mind that, India is a large country having its border with many countries. People in the sub-continent have a common history and share many similarities in physical looks. Due to various reasons including political or economical, inimical reasons, some people from neighboring countries may enter India. May be due to some cultural and ethnic similarities, on many occasions such migrants go unnoticed and they almost willing and try to settle in our country. These illegal migrants sometimes pose threat to the national security, and infringe the rights of Indian citizens. It should also be borne in mind that now-a-days terrorism has become serious concern for most of the nations. Illegal migrants who enter Indian Territory with obvious motives to cause damage to the national security are more vulnerable. It is also evident from various instances which happened in India, that some miscreants have recruited Indian citizens to their organizations for their wrongful gain, in turn to cause wrongful loss to Indian territory. We have very bitter examples of infiltrators inhuman acts at Jammu and Kashmir, Rohingyas in State State of Myammar. The retaining of the illegal migrants may be some times helpful to the country if they came to our country eking their lively hood and they are all from hard working community. But, that does not mean to say that for that reason, they can be retained in India in violation of the various Acts and Rules of the Country.

Why in the news?

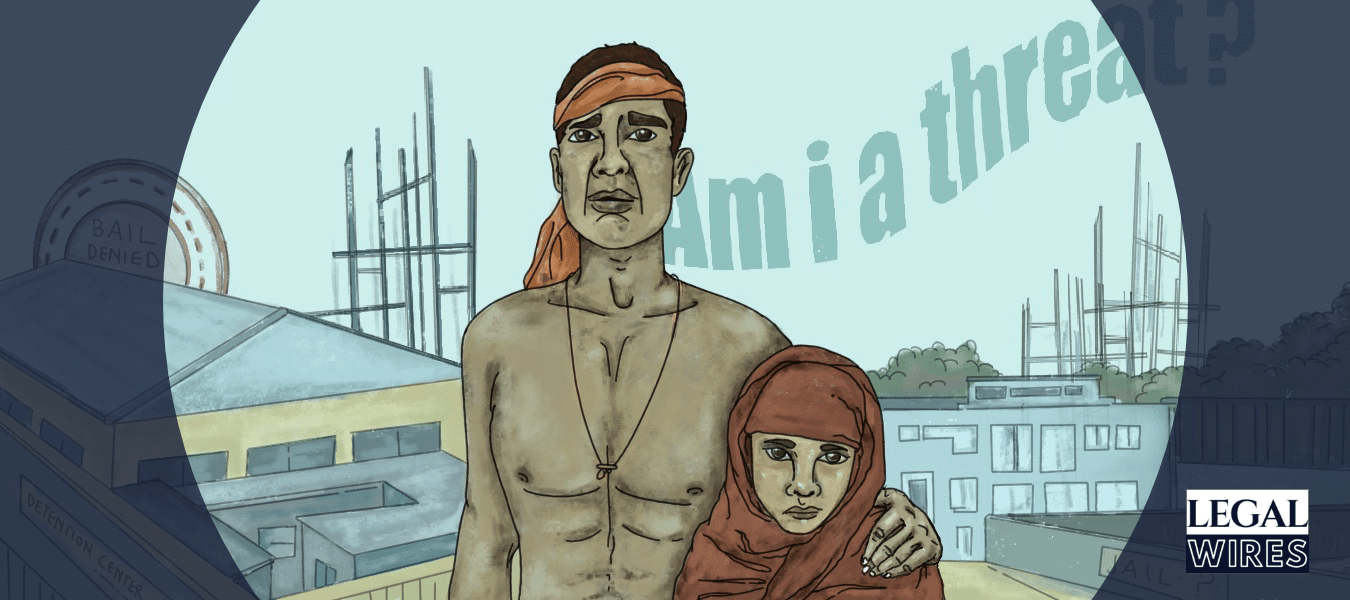

The bail application was pertaining to a father-daughter duo: rag pickers by profession ( who had spent 1 year in jail as undertrials ), accused of being illegal migrants from Bangladesh by the Police and charged under Section 14 and Section 14A of the Foreigners Act, 1946 as well Section 25 of the Arms Act, 1959 for having possession of empty cartridges. The single-judge bench of Justice K.N. Phaneedra, laid down certain guidelines with regards to the procedures to be followed when an offense has been alleged to be committed by a person who is an illegal immigrant, as well as on the treatment of such illegal immigrants (specifically women and children) till they are deported to their country.

The 127 pages bail order, dealt with the sources of such guidelines particularly the 2007 case of R.D Upadhayay v. State of Andhra Pradesh[1], the Prison Manual, Prison Act and State Rules extending the application of all guidelines meant for inmates of prison to the foreigner inmates of detention centers and prisons. However, the justification for the extension of such guidelines for jails to Detention Centres, have not been dealt with.

It has been an established principle of Indian courts that the status of a person’s country of origin or nationality has no relevance when it comes to the determination of their bail applications.[2]

The bail order has drawn several criticisms for directing that the illegal migrants (or accused of being illegal migrants) to be kept in Detention centers mandatorily, with in-house 24/7 monitored surveillance and State-controlled discipline, even after they have been granted the bail or are acquitted from such charges. If bail order is not granted or they are convicted of the offense, then, in that case, such persons must be kept in prisons.

Such an order, unfortunately, runs in a trajectory opposite to the jurisprudence on Bail. Bail has been defined as: “The process by which a person is released from custody,” not a transfer of custody from one place to another. By giving a connotation that persons (declared or accused of) being illegal migrants must have a different meaning for Bail, whereby it shall mean not release but rather a transfer of custody, is a dangerous and lousy proposition in law.

The bench while accepting the contentions of the State government’s draft and initiative to establish permanent and temporary detention centers, did fail to ascertain the ground realities of such detention centers, which as of late has been pointed out in several media reports[3] and surveys to be in deplorable conditions. In this context, the observations of Justice Krishna Iyer, in the case of Babu Singh v. State of Uttar Pradesh[4], hold relevance:

“Equally important is the deplorable condition, verging on the inhuman, of our sub-jails, that the unrewarding cruelty and expensive custody of avoidable incarceration make the refusal of bail unreasonable and a policy favoring release justly sensible……Thus, conditions may be hung around bail orders, not to cripple but to protect. Such is the holistic jurisdiction and humanistic orientation invoked by the judicial discretion correlated to the values of our constitution.”

By extending Upadhayay guidelines and drawing inspiration from Prison Rules, the Court has, unconsciously, conflated in legal terms the difference between the Prison and Detention Centre to mean the same thing. However, in common parlance and ground realities of inhumane conditions[5], they already do hold a reputation to be synonymous entities. Still, an unconscious acknowledgment in terms of judicial directives is an issue that calls for introspection and scrutiny from the judiciary. Especially when the Supreme Court has taken cognizance of such deplorable conditions of Detention centers in a PIL filed by Harsh Mander.

Problem with the Controversial observation of the Bench

Though there are several issues with the judgment, attracting critical scrutiny from different quarters, the most problematic is the para 14 (mentioned above). A prejudice is evident on the face of it, wherein a generalization of illegal migrants (specifically Rohingya community) has been made, when the bench blatantly brandishes a whole class of persons as potential terrorists. One can find the vestige of colonial hangover of the Criminal Tribes Act, 1924 in the above statement, wherein the State authorities (and even Courts) would specifically term and declare entire communities as criminal. An accidental birth in that community itself was sanctioned as a heinous crime. .

Under Criminal Tribes Act, 1871 (as well as in its 1924 version) once a tribe was ‘notified’ as criminal, all its members were forced to register themselves with the authorities and give Hazri (attendance) at a specified time of the day or as demanded. The people belonging to that community did not possess the right to movement, were constantly placed under State-surveillance and suspicion; and constantly subject to draconian scrutiny and punishment by police and authorities. Though repealed in 1952, the stigma around such ‘Criminal tribes’, now called ‘Denotified Tribes’ still looms over the institutional process.

Although much water has flown over, with India adopting its Constitution (heavily influenced by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), which has constitutionally invalidated any such discrimination or prejudice in light of Article 14, it must be noted that Article 14 extends to both citizens and non-citizens alike.

India ratified the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) on 3rd December 1968, wherein under Article 5(a), all human beings have “The right to equal treatment before the tribunals and all other organs administering justice.” The Article casts a duty upon the courts and tribunals of India, to treat all persons alike. The adjudication of their case or status must not be based on any form of prejudice or positive discrimination that fails the ‘intelligible differentia’ test, which must form a ‘reasonable nexus with the object.’

The object of Security threat, however, in this context, happens to be outside the purview of the judicial domain. Even if the Judiciary does out-maneuvers a jurisdiction over the issue of National Security, under the garb of its unchartered tradition of ‘Judicial Overreach’; induction of an entire population as ‘potential’ terrorists and ‘security threat’ is an abominable proposition when tested on the touchstone of Constitution and Human Rights jurisprudence.

It must be noted that no material was placed on record for the bench to arrive at such a predisposed conclusion. Neither any such sources were referred by the court to substantiate its claim that, “ It is also evident from various instances which happened in India, that some miscreants have recruited Indian citizens to their organizations for their wrongful gain, in turn, to cause wrongful loss to Indian territory.” In the Supreme Court case of Mohammad Saimullah & Anr v. Union of India & Ors.[6], similar claims have been made in the Affidavit filed by the Central Government, the validity of which is still disputed (the Government is yet to substantiate and establish its claims), and a definitive conclusion to that issue is yet to be espoused by the Supreme Court. However, media reports have refuted any terrorist attacks or involvement of Rohingyas or other illegal migrants in any terror conspiracies against the Indian state.[7] So far, no terrorist attacks have been linked to the Rohingyas or illegal migrants. In the dearth of any such sources, which could substantiate the sweeping claims made by the bench, it can be reasonably attributed that the bench had fallen victim to the ‘Fake Propaganda’ instituted by the miscreant elements of some mainstream political outfits. The claim of the bench happens to mimic both language and contents of the widely circulated canard on social media such as Watsapp and Facebook, which was directed against Anti-migrant sentiments and Rohingyas in recent past.[8]

In today’s age of digital social fake news/propaganda and media hyperbole, which has plagued and distorted the world view of individuals on hard-lines of the disseminators’ schemes, it would be unfair to expect that the Courts could remain unaffected by it. They might err on several instances, for in today’s digitally driven world climate, it becomes excruciatingly hard to differentiate between genuine and false information. It would be suggested that Courts must craft some mechanism to filter such content from overarching onto judicial reasonableness and even in public discourse at large.

It is a general rule of prudence that, to claim something to be ‘evident,’ the Courts must first ascertain the ‘evidence.’ The Courts can make ‘reasonable’ presumptions, as per Section 114 of the Indian Evidence Act,1872, but that too needs to be substantiated for its ‘reasonableness.’

The pits of ‘prejudice’ destroy the credibility of judicial institutions. It must be noted that the word ‘prejudicial’ is an antithesis of the word ‘judicial.’ The term ‘Judiciary’ itself is driven from the word ‘judicial’ which means ‘reasonableness’ or ‘prudence.’ Thus, Judiciary cannot claim its sanctity as temples of judicial reasoning if they fall victim to prejudices.

Such anti-migrant rhetoric statements must not find a place in any state institution, more so ever in any judicial forum. While the intention of the bench should not be doubted solely based on a few observation statements, but the comments made as such must be condemned.

The bench did happen to concern itself with issuing guidelines for directing better conditions of such undertrial persons accused of being illegal migrants. In para 93 it has stated,

“It is just necessary to say that in the present-day situation, considering the great traditions of our country as to how we are treating, respecting and taking care of women and children, particularly so far as the prisoners are concerned much care has to be taken if possible to avoid any social stigma that may be attached to women living in prison or Detention Center, as the same often severely affect and attach stigma upon them even after they are released.“

But the fact, that the bench happens to be far more concerned about the social stigma of such women and children, who happen to be (or accused of to be) illegal immigrants than their liberty to participate in the society, is absurd.

For social stigma to exist, first, the individual must participate in society. When the bench gave the directive that if such person is acquitted or bailed, they shall be ‘mandatorily’ be kept in Detention Centres unless the Competent authority of the Central or State Government grants them permission to be released; or when such a person is convicted or denied bail, they must be kept in jail; it, unfortunately, left no room for such persons to have a legal recourse to plead to participate in the society. Perhaps the bench was unmindful of such implications of its judgment. Still, in practical terms, a far more concern for ‘social stigma’ than such person’s liberty in a bail order (It must be noted that nowhere in 127 pages, personal liberty of the person is discussed, and this is a bail order which urged a mandatory discussion on personal liberty) serves as a crude mockery of the conditions of such accused persons.

[1] (2007) 15 SCC 337

[2] Bijoylashmi Das, India: Bail, A Matter Of Right: Not To Be Denied On The Ground Of Nationality, Source Link. (accessed on 10th June, 2020)

[3] For more information watch the report coverage “Inside Assam’s detention centres for ‘foreigners’ – despair & appalling living conditions”, The Print, Source Link (accessed on 10th June, 2020) ; Inside Assam’s Detention Camp: ‘Its Like Hell’ (BBC Hindi) reported on August 23, 218, Source Link ; “Detention Camps of Assam: The Inside Story of Death, Despair and Broken Dreams | The Quint” reported on 10 December, 2019, Source Link (accessed on 10th June, 2020)

[4] 1978 AIR 527

[5] Inhumane Conditions in Assam Detention Camps, Alleges NELECC Civil Society, reported on 30 June, 2018, Source Link (accessed on 10th June, 2020)

[6] Writ Petition (Civil) No.793 of 2017

[7] For more information read INDIA’S ROHINGYA TERROR PROBLEM: REAL OR IMAGINED? Published on

December 1, 2017 by Mohammed Sinan Siyech Source Link (accessed on 10th June, 2020)

[8] Rohingya refugees are eating flesh of Hindus, Fake news: Sonia Gandhi in bikini, Rohingyas eating Hindus & Nehru calling Bose a criminal reported on 14 April, 2019 Source Link (accessed on 10th June, 2019)