– Shivani Chauhan, Mohammad Adil Ansari Introduction When we look

– Shivani Chauhan, Mohammad Adil Ansari

Introduction

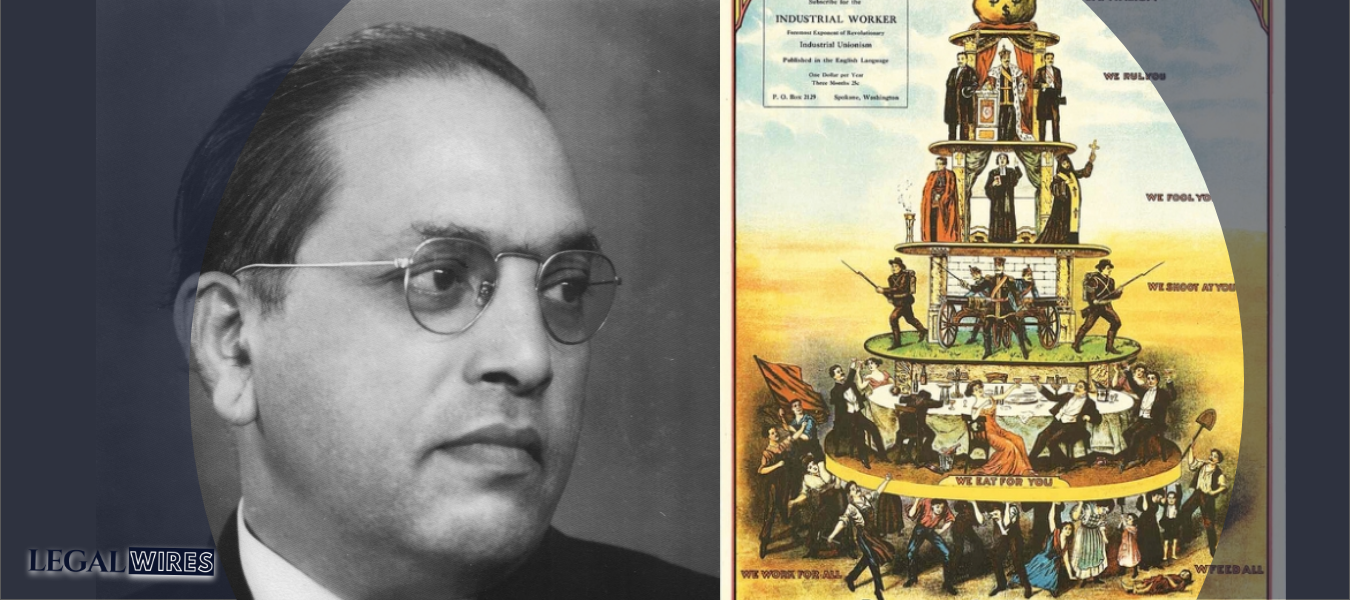

When we look at the character of the Indian Constitution, the word ‘Secular’ in the Preamble generates a peculiar interest around its theoretical disposition and functional importance in the Indian context. A wide range of academic work as well as political sensibilities have been generated around it, to extract the profound meaning of the word. The western conception of the doctrine, which expounds ‘Separation of State and Church’, has long been refuted by the framers, Baba Saheb Bhim Rao Ambedkar included. The answer to the exact position of the doctrine is not that simple to be enunciated in plenary words with exact precision. It cannot be termed simply as a State which is the antithesis of Religion, for that shall amount to abdication of the socio-cultural character of Indian milieu, one of the many reasons why the word ‘Secularism’ was intentionally omitted from the Constitution.

Dr. Ambedkar wanted to establish India into a secular state but in the absence of a philosophical and theoretical refinement that suited Indian society, he opposed the inclusion of the word in the Preamble. Though its brooding was established in the constitutional framework by the inclusion of Article 25, 26, and 27. To understand what were the aspirations of Dr. Ambedkar with regards to the doctrine, it becomes essential for a study of his disposition on religion and his ideological rooting and viewpoints. Dr. Ambedkar’s work on religion has not been exposited foremost, much because of the infatuation of academia with his work on criticism of the caste system.

Dr. Ambedkar had a very divergent and unique view on religion which was in complete contrast to the prevailing religious question in India, which had been historically reduced to a “Hindu-Muslim question”. It was in fact also opposed to the views of modernists and progressives like Nehru, who relegate religion to be of no social importance in a modern state – the liberals insisting that religion is or should be a matter of private faith and Marxists by insisting that religion is false consciousness of people who do not recognize their own true economic interest.

His views were rather a harmonizing construct between two divergent views of one criticizing religion for being a divisive or irrational force, and others such as Gandhi who felt that all religions were true and worthy of respect.

Modern-day states have a pervading presumption that religion has become rather an obsolete phenomenon after the Enlightenment era. It has been discarded and relegated to the position of superstition of primitive societies. But the recent resurgence of religious extremist episodes from Zionist Movement to Islamic fundamentalism to Hindutva brigade are livid examples which point to the shallowness of such a presumption.

Apart from the Enlightenment era, Marxism has had the most profound influence on such a political secular character of State. Marxist ideology believes religion to be a superstructure construct to hide the underlying class struggle. Marxists consider religion to be a weapon of the ruling class to subdue the working class, ‘an opium of the masses’ to keep the latter in a constant state of intoxication so they shall not rationalize to be able to realize and rise against the sufferings imposed upon them by the ruling class. The ideology believes in complete annihilation of religion from the public domain, and to limit it (or possibly eliminate it) not beyond the domain of individual private space. They believe religion to be a hindrance to the scientific and communist society. In his book ‘Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right‘, Marx expounds: “The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo.“

Going by the earlier writings of Dr. Ambedkar, we find that Baba Saheb was quite intrigued by the Marxist idea on religion. The greatest testament to this fact is that on 2 December 1956, just four days before he died, Dr. Ambedkar wrote an article “Buddha or Marx“, juxtaposing the ideological contrast between the two intellectual giants. He wrote extensively during his lifetime on several religions including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. He was greatly inspired by the work of Marx and found similarities with Marx’s analysis to his own experience of the rigid caste system and religious practices in India. It was Marx’s revolutionary criticism and proposition of disbandment of religion in a social sphere which perhaps inspired Dr. Ambedkar to adopt a revolutionary approach to lay an open challenge to Hinduism and Brahmanical hegemony over the religious affairs. When he said “I have no country,” to Mahatma Gandhi, his words had resonance with Marx’s famous statement that the working classes have no country.

But we cannot simply stretch to refer Baba Sahib as a Marxist, as he deviated on many points and occasions from the Marxist Idea. Unlike Marx, who wanted the total abdication of religion in society, Dr. Ambedkar rather recognized the relevance and importance of religion and his academic work and political and social life were mainly concerned at reforming the evils pervading the society in the name of religion. The paper seeks to address the contrast between the two viewpoints over their points of interjection and deviation and shall explore why the Ambedkarite idea was more pragmatic than the Communist idea to reform the Indian religious society.

The discourse finds its relevance today as his works have helped us develop both a critique and an understanding of religion as a phenomenon.

Marxist’s idea of Religion

Making the class conflict as the base of his philosophy, Karl Marx, the founder of Communism, idealized a communist state ruled by proletariats to be a Utopian society in every aspect. Marxist believe that Communism is inescapable and inevitable and that society is moving towards it and that nothing can prevent the march. And in order to achieve it, all superstructural hindrances that guise and concretize the underlying class conflict need to eradicated.

Marxists believe religion to be an epitome of such superstructures. To them, all religions are essentially suicidal for the achievement of the utopian communist state, as they act as the “illusionary sun which revolves around man as long as he does not revolve around himself (and his miserable condition)”. They believe that religion is of particular utility to the bourgeois class as it gives the proletariat (working class) false hope for millennia and false illusionary justification for their condition and position in life. In fact, it acts as a buffer that prevents them from realizing and questioning their misery and exploitation. Terming it as an ‘opium of masses’, Marx called for the complete abdication of religion from the public sphere.

For the purpose of our discourse, we shall take the following principles of Marxism into consideration:

- Marxist believe that the forces which shape the course of history are primarily economic.

- The exploitation of the working class can be put to an end by the nationalization of the instruments of production i.e. abolition of private property.

- Violence and Dictatorship of the Proletariat are the necessary means for achieving a communist state.

- The purpose of philosophy is to reconstruct the world and not to delve into the metaphysical realm to explain the origin of the universe.

Dr. Ambedkar’s views on Marxist idea of religion

In his paper ‘Buddha or Karl Marx’, Dr. Ambedkar has vehemently established the superiority of Buddhism over the Marxist theory. It ought to be considered at this point that for Dr. Ambedkar, all religions were not equal. Unlike the Marxists, who sweepingly consider all kinds of different faiths as synonymous units of a single superset of Religion, Ambedkar had a rationally opposite view. In his article titled ‘Conversion‘ written following the Mahar Conference in 1936, he establishes his claim that all religions are not equal. In his words:

“Religions may be alike in that they all teach that the meaning of life is to be found in the pursuit of ‘good’. But religions are not alike in their answers to the question ‘What is good?’ In this they certainly differ. One religion holds that brotherhood is good another caste and untouchability is good.

There is another respect in which all religions are not alike. Besides being an authority which defines what is good, religion is a motive force for the promotion and spread of the ‘good’. Are all religions agreed in the means and methods they advocate for the promotion and spread of good?………..Apart from these oscillations there are permanent difference in the method of promoting good as they conceive it. Are there not religions which advocate violence? Are there not religions which advocate non-violence? Given these facts how can it be said that all religions are the same and there is no reason to prefer one to the other”[1]

According to him religion was essentially different from theology, with the former consisting primarily of usages, practices and observances, rites and rituals. The theological part of such rituals was secondary and developed later to rationalize such usages and observances.

When it comes to the domain of religion, Marxist view refute its relevance in the public domain and consider it merely a personal affair of an individual. Dr. Ambedkar considered it a flawed view. He believed that it is a mistake to look upon religion as a matter which is individual, private and personal. He said, “The correct view is that religion like language is social for the reason that either is essential for social life and the individual has to have it because without it he cannot participate in the life of the society.”[2]

Emphasizing that religion universalizes the social values, Ambedkar said that they are required by the individual to be recognized in all his actions so that he may qualify to function as an approved member of the society. He lent his support the views of Professor Ellwood regarding functions of religion, who expounded that religion is

“to act as an agency of social control, that is, of the group controlling the life of the individual, for what is believed to be the good of the larger life of the group……The function of religion is the same as the function of Law and Government. It is a means by which society exercises its control over the conduct of the individual in order to maintain the social order……. As compared to religion, Government and Law are relatively inadequate means of social control. The control through law and order does not go deep enough to secure the stability of the social order. The religious sanction, on account of its being supernatural has been on the other hand the most effective means of social control, far more effective than law and Government have been or can be. Without the support of religion, law and Government are bound to remain a very inadequate means of social control. Religion is the most powerful force of social gravitation without which it would be impossible to hold the social order in its orbit.”[3]

It is because religion has a social function, Dr Ambedkar believed that a person has a right to question its viability as to how well it served that individual socially. He should have the right to ask how well it has served the purposes which belong to religion.

He was therefore critical of the Communist disposition on religion and considered it a narrow interpretation that neglected the essential significance of different religions in different communities. In ‘Buddha or Karl Marx’, he writes,

“But to the Communists religion is anathema. Their hatred of religion is so deep-seated that they will not even discriminate between religions which are helpful to Communism (such as Buddhism) and religions which are not. The Communists have carried their hatred of Christianity to Buddhism without waiting to examine the difference between the two. The charge against Christianity levelled by the Communists was two -fold. Their first charge against Christianity was that they made people other worldly and made them suffer poverty in this world. As can be seen from quotations from Buddhism in the earlier part of this tract such a charge cannot be levelled against Buddhism.“[4]

Dr. Ambedkar was deeply inspired by the Buddhist philosophy, which is well reflected in his works and life. Considering it as a religion of modern world, he would base all his analysis of religion on its touchstone. In his article ‘Buddha or Karl Marx’, he drew a parallel contrast between the two. He said Buddhism and Marxism shared some basic concepts– such as considering private property to be the source of all inequalities (hence the Buddhist conception of the bhikshu and the Marxist conception of the proletariat, referring to those who have nothing to lose and therefore those who potentially are the real force of change). But Marxism parts ways with Buddhism, because having wished away religion as the “opium of the people“, it inevitably turns to the State as the primary instrument of social change (as did, in his times, both Soviet and Chinese socialism, Kamâl Atatürk‘s Kemalism and Nehruvian socialism). The result, as we know, often morphed its way into fanaticism, dictatorship, and violence. To ensure equality, thus, Marxism chooses to sacrifice liberty.

Ambedkar contrasts the “dictatorship of the proletariat” with the ancient Buddhist sangha, which, according to him, institutionalized democratic governance of those who voluntarily entered the community of the adept. Buddha, he said, was more flexible about the principle of non-violence than he was about the principle of democracy.[5]

Dr. Ambedkar acknowledged that much of the ideological structure raised by Karl Marx had broken into pieces. The Marxist claim that socialism is inevitable has been completely refuted and disproved. With the exception of Russia and China, the rest of the world is yet to witness the coming of the Proletarian Dictatorship, both of which have now taken the crossroads which itself interject into the path of global capitalism. Besides, it is no longer an accepted view that the economic interpretation of history (as propounded by Marx) is the only valid explanation of history. Thereby Ambedkar refutes point no. 1 and point no. 3 of the abovementioned pointers of Marxism.

However, Ambedkar acknowledges the relevance of point no. 2 and point no. 4, and is in agreement that the function of philosophy is to reconstruct the world and not to waste its time in explaining the origin of the world. He believes that private property is the chief cause of exploitation and acknowledges the presence of a class conflict. The validation provided by Ambedkar to these points bear a heavy influence of Buddhism on his psyche, which he profoundly acknowledges in the article.

With regards to point no. 2, he draws a parallel between Buddha and Marx, claiming that Buddha was in fact the first one to recognize the class conflict, and it being the root cause of misery. The doctrine of Ashtanga Marg recognizes this class conflict and thereby seeks to eliminate it by changing the disposition of men regarding the material luxuries of life. Thus, the end which both Buddhism and Marxism seek is in fact the same. However, there is a difference between the means both expound for the achievement of this end. Buddhism enunciates the philosophy of non-violence (Ahimsa) and seeks to change the disposition of man in order to achieve this end. While Marxism stresses on State to be the chief architect of bringing about such a change, by abolishing private property and nationalization of all such property, to be accompanied by violence and dictatorship if necessary.

Dr. Ambedkar was in strong disapproval of dictatorship of a permanent character. He however did admit the benefit of temporary dictatorship provided if it was in the cause of safeguarding democracy. A viewpoint which we find enacted in the Part XVIII of the Indian Constitution which dealt with the ‘Emergency Provisions’. In his words, “Dictatorship for a short period may be good and a welcome thing even for making democracy safe. Why should not dictatorship liquidate itself after it has done its work, after it has removed all the obstacles and boulders in the way of democracy and has made the path of democracy safe.“[6]

He derived the theological approval of his stand for democracy from Buddhism as Buddha was a thorough equalitarian. He writes that Buddha was a born democrat and he died democrat. The Sakya kingdom he belonged was a republic. “The Bhikshu Sangh had the most democratic constitution. The Buddha was only one of the Bhikkus. At the most he was like a Prime Minister among members of the Cabinet. He was never a dictator. Twice before his death he was asked to appoint someone as the head of the Sangh to control it. Buch each time he refused saying that the Dhamma is the Supreme Commander of the Sangh. He refused to be a dictator and refused to appoint a dictator.“[7]

Conclusion

It is evident from the abovementioned analysis that Ambedkar’s rethinking of religion cannot be understood within liberalism’s framework of secularism and religious tolerance. His method was innovative, critical and much more pragmatic. He was in agreement with certain ideals of communism but completely refuted their means of achieving such ends. By saying, “Humanity does not only want economic values, it also wants spiritual values to be retained“[8], he acknowledges the aspirations of communism to create an equalitarian society, but that alone cannot be the basis of sustenance of society. He welcomed the Communist movement because it aimed to produce equality, but he said, “it cannot be too much emphasized that in producing equality, society cannot afford to sacrifice fraternity or liberty. Equality will be of no value without fraternity or liberty.“[9]He believed that all these three can be achieved only by following the Buddha. Communism can only give equality but it comes at the cost of sacrificing fraternity and liberty, thus it may have practical significance in backward countries, but it is unsustainable and undesired in the long run.

For India though, the recent political discourse which has hard-lined itself around the flawed binary of Western Secularism vs Hindutva debate, an introspection and reconstitution of the such a narrative is required, much in lines with the philosophical position of such intellectual giants who have attempted and demonstrated the confluence and contradiction between the Western and Eastern ideals. Dr. Ambedkar’s ideas become more important in such a climate.

[1] Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Conversion, Page 4

[2] Supra Page 7

[3] Supra Page 9

[4] Dr. B. R. Ambedkar, Buddha or Karl Marx, Page 15

[5] Prathama Banerjee, Ambedkar’s rethinking of religion, Source Link

[6] Supra 4, Page 15

[7] Supra 4, Page 13

[8] Supra 4, Page 17

[9] Supra 4, Page 17