This article explores the concept of strict liability within the framework of tort law. Strict liability imposes liability for harm caused by an ultra-hazardous activity, even in the absence of negligence. The seminal case of Rylands v. Fletcher will be examined to illustrate the key elements of thi

Introduction

Tort law, a branch of civil law, seeks to provide compensation to those who suffer harm due to the wrongful conduct of others. Consider a hypothetical scenario where someone gets hurt because of an activity, but the person responsible wasn’t careless or malicious. In such cases, the law might hold them liable anyway. This concept is called “strict liability” or “no-fault liability.“

Strict liability applies to situations involving ultra-hazardous activities. These activities have a high risk of causing serious harm if something goes wrong. Even if the person takes all reasonable precautions, they can still be held responsible for any damage that occurs. The idea of strict liability has emerged from various English case laws and the same has evolved the Indian law with regards to the principle of strict liability.

Establishment of the concept of Strict Liability- Rylands v. Fletcher, 1868

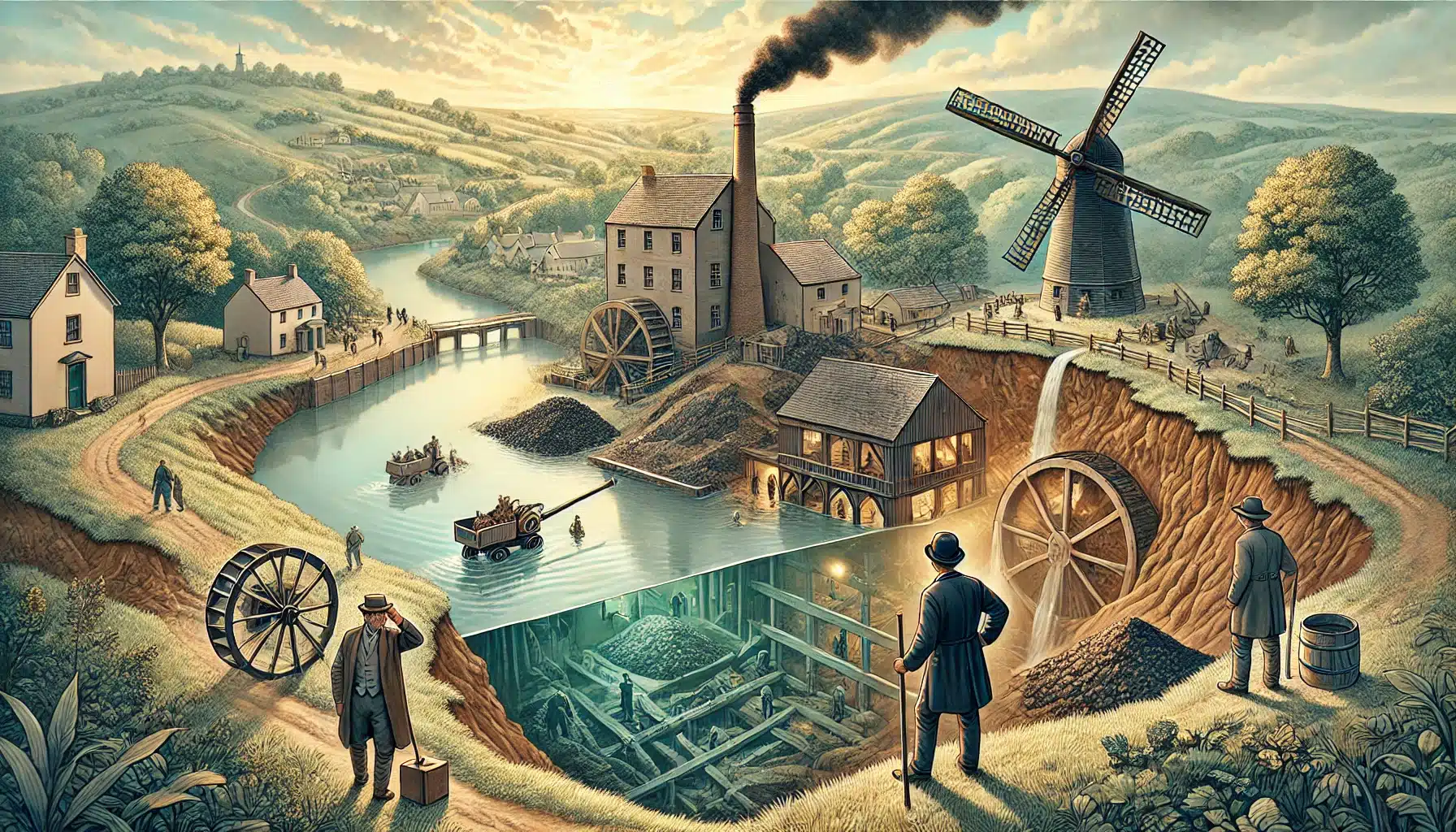

In 1868, a landmark case named Rylands v. Fletcher[1] established the foundation for strict liability in English common law.

● Facts: The defendant, a mill owner, contracted independent builders to construct a reservoir to supply water for his mill. Unbeknownst to them, the chosen site contained hidden, defused mine shafts. The builders did not identify these shafts, and they remained unblocked. When the reservoir filled with water, it seeped through the undetected shafts and flooded the adjoining coal mine owned by the plaintiff. The defendant (the mill owner) wasn’t aware of the shafts and wasn’t directly negligent in their construction.

● Ruling: The House of Lords held the defendant liable for the damages, even though they were not negligent in constructing the reservoir. The court reasoned that someone who brings a dangerous thing onto their property and keeps it there is liable for the harm it causes if it escapes.

The rationale behind the Strict Liability

● Justice Blackburn provided the rationale behind the defendant’s liability. He stated that if someone brings something inherently dangerous onto their property and keeps it there, they become liable if it escapes and causes harm.

● The critical factor is the hazardous nature of the thing itself. In this case, the large volume of water was considered dangerous. If it escaped, it had the potential to cause significant damage, as it ultimately did. Justice Blackburn acknowledged that defenses exist to avoid strict liability, but none applied in this case. Therefore, the defendant could not escape responsibility.

The Principle of Strict Liability

This case established the principle of strict liability. Strict liability means that someone can be held legally responsible for harm caused by a dangerous thing on their property, even if they weren’t negligent. In simpler terms, if you keep something dangerous and it escapes, causing damage, you’re generally liable, regardless of your actions.

The Three Pillars of Strict Liability

The landmark case of Rylands v. Fletcher (1868) established a crucial principle in tort law: strict liability. This principle holds a defendant liable for damages caused by an ultra-hazardous activity on their land, even if they weren’t negligent.

To understand when strict liability applies, we need to consider three key elements:

- Dangerous Thing: The defendant must keep something inherently dangerous on their property. This can be a variety of things, but courts typically consider substances like explosives, large quantities of flammable liquids, or even abnormally dangerous animals to fall under this category. In Rylands v. Fletcher, for instance, the sheer volume of water stored in the reservoir was deemed inherently dangerous.

- Escape: The dangerous thing must escape the defendant’s control and cause harm; mere keeping of a dangerous thing is not sufficient to hold a person liable. This escape can be physical, like the water overflowing the reservoir in Rylands v. Fletcher, or it can be a consequence of the dangerous thing’s nature. For example, harmful fumes escaping from a factory can also be considered an escape.

- Non-Natural Use of Land: The land must be used in a way that’s not ordinary or customary. Activities like storing large amounts of explosives or building a reservoir on private property are typically considered non-natural uses. This element helps distinguish strict liability from negligence claims. Everyday activities with minimal risk generally wouldn’t trigger strict liability.

For example, In Rylands v. Fletcher, 1868,[2] water collected in a massive reservoir was regarded as a ‘non-natural’ use of land. There was the case of Sochacki v. Sas,[3] in which it was held that the liability that arose in Rylands v. Fletcher could not arise if the fire in a house in a grate[4] occurs since it is an ordinary and natural use of land. Some of the activities that might be regarded as non-natural use of land but they are not:

● Electric Wiring around a house or a shop.

● Supply gas in the dwelling house through gas pipes.

● Installing water in houses.

Act of an independent contractor

In most cases, the employer escapes from liability when an independent contractor performs the act; however, when it comes to the Strict Liability clause, the employer cannot seek this as a defense, and as pointed out in Rylands v. Fletcher, the defendant is liable despite the fault of an independent contractor.

A similar observation was made in T.C. Balakrishnan Menon v. T.R. Subramanian[5], where the facts of the case were that an explosive was made out of a coconut shell filled with an explosive substance. The explosive did not explode then and there but instead went somewhere else and exploded amidst the crowd, injuring the respondent in the process. The question that arose before the court was whether the appellant would be held liable for engaging an independent contractor to attend the fireworks exhibition. The court held that since the explosive is an ‘extra hazardous’ substance, the rule of Strict Liability would be implemented, and as a result, the appellant was held liable.

Exceptions to Strict Liability

There are certain situations wherein a defendant can escape liability under strict liability rules. The defendant is entitled to five types of defense; here’s a breakdown of these exceptions.

- Plaintiff’s fault

If the plaintiff’s actions directly caused the harm, the defendant may not be liable. For example, if someone lets their horse wander onto another’s property, where it eats poisonous plants and dies, the landowner wouldn’t be responsible, as elucidated in Ponting v. Noakes.[6]

Similarly, if someone lays cables in an unusual way and suffers damage due to electric current from a tram line, they may be unable to claim against the tram company. (South African Telegraph Co. Ltd. v. Cape Town Tramways Co.[7])

- Act of God

If an unforeseeable natural disaster causes the escape of a dangerous substance and results in damage, the defendant might not be held liable. In Nichols v. Marsland[8], a reservoir was built with proper precautions. An extraordinary amount of rainfall caused the dam to break, flooding the nearby property. The “Act of God” defense was applied in this case, and the defendant was held not liable.

- Plaintiff’s consent

If the plaintiff knowingly agrees to the presence of a dangerous thing on the defendant’s property, they might not be able to claim damages if it escapes and causes harm.

For instance, in Carstairs v. Taylor[9], the plaintiff, who rented the ground floor of a building from the defendant (who resided upstairs), sued for damages after a leak in the upper floor damaged their belongings. The leak occurred from a water source intended for the shared use of both parties. The court, however, ruled in favor of the defendant. Since the water storage served the mutual benefit of both tenant and landlord, and there was no evidence of negligence on the defendant’s part, liability could not be established.

- Act of a third party

If the escape of a dangerous thing and resulting harm are caused by the unforeseeable actions of a third party beyond the defendant’s control, they may not be liable. For example, an electricity company might not be held responsible if a snapped wire causes electrocution during a storm, provided they took reasonable precautions and the snap couldn’t have been foreseen. (M.P. Electricity Board v. Shail Kumar[10]) However, if the defendant should have anticipated the third party’s act, this defense wouldn’t apply.

- Statutory authority

If someone acts under the lawful instructions of a statute, they might be exempted from strict liability if they act within the legal permissions. The landmark case of Green v. Chelsea Waterworks Co.[11] involved a water company legally obligated to supply water constantly—unfortunately, a water main burst, flooding the plaintiff’s property. However, the company wasn’t found liable because they were fulfilling their legal duty to provide water.

Position in India

The principle of ‘Strict Liability’ finds its application within the Indian legal system as well. However, the scope and restrictions of this principle have evolved over a period of time that seeks to maintain a balance between industrial developments and compensating the victim.

- Motor Vehicle Accidents

Earlier judgments, like Minu B. Mehta v. Balakrishna (1977)[12], required proving negligence on the vehicle owner or driver to claim compensation. However, the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 introduced a limited form of “no-fault liability.” For accident victims sustaining death or permanent disability, a fixed sum can be claimed without establishing fault. This reflects a move towards a stricter liability regime in motor accidents, recognizing the inherent dangers involved.

- Railways and Carriers

Until 1961, railways were liable as bailees under the Indian Contract Act, meaning they were only responsible for harm if they failed to take proper care of goods. However, an amendment transformed their liability to that of an insurer. Similarly, the Carriers Act, 1865 establishes strict liability for common carriers transporting goods by land.

Exceptions: Balancing Necessity with Liability

● While strict liability exists in certain areas, exceptions acknowledge practical realities. Storing large quantities of water for agriculture, which is crucial in India’s context, is one such exception. The case of Madras Railway Co. v. Zamindar (Privy Council)[13] recognized this.

● Here, overflowing water from ancient tanks used by thousands did not automatically trigger strict liability. The court reasoned that the immense social benefit of such water storage outweighed the risk, placing the onus on the owner only to take reasonable precautions to prevent harm. A similar approach was adopted by the Andhra Pradesh High Court in K. Nagireddi v. Government of Andhra Pradesh (2000)[14].

Conclusion

Strict liability is a powerful deterrent, encouraging those engaged in ultra-hazardous activities to prioritize safety measures and risk management. The exceptions have been laid down to prevent overly harsh outcomes and acknowledge certain inevitabilities of the world. For instance, unforeseeable natural disasters are uncertainties, and the person should not be held liable for the damages occurring because of such disasters.

Furthermore, exceptions for activities deemed crucial for societal well-being, like water storage in some regions, demonstrate a willingness to balance risk allocation with social progress. This nuanced approach ensures that victims are justly compensated and essential activities are not unduly hindered.

Strict liability fosters a dynamic legal framework that promotes responsible conduct while allowing advancements to flourish. It compels polluters to pay while ensuring that innovation and societal progress are not stifled. The strict liability principle serves as a keystone to ensures a balance between societal and industrial development.

[1] (1868) L.R. 3 H.L. 330.

[2] ibid.

[3] (1947) 1 All E.R. 344.

[4] R.K. Bangia, The Law of Torts (Twenty Second edition, Allahabad Law Agency).

[5] A.I.R. 1968 Kerala, 151.

[6] (1849) 2 Q.B. 281.

[7] (1902) A.C. 381.

[8] (1876) 2 Ex. D. 1.

[9] (1871) L.R. 6 Ex. 217.

[10] A.I.R. 2002 S.C. 551.

[11] (1894) 70 L.T. 547.

[12] A.I.R. 1977 S.C. 1248.

[13] (1974) 1 I.A. 364 (P.C.).

[14] A.I.R. 1982 A.P. 119.