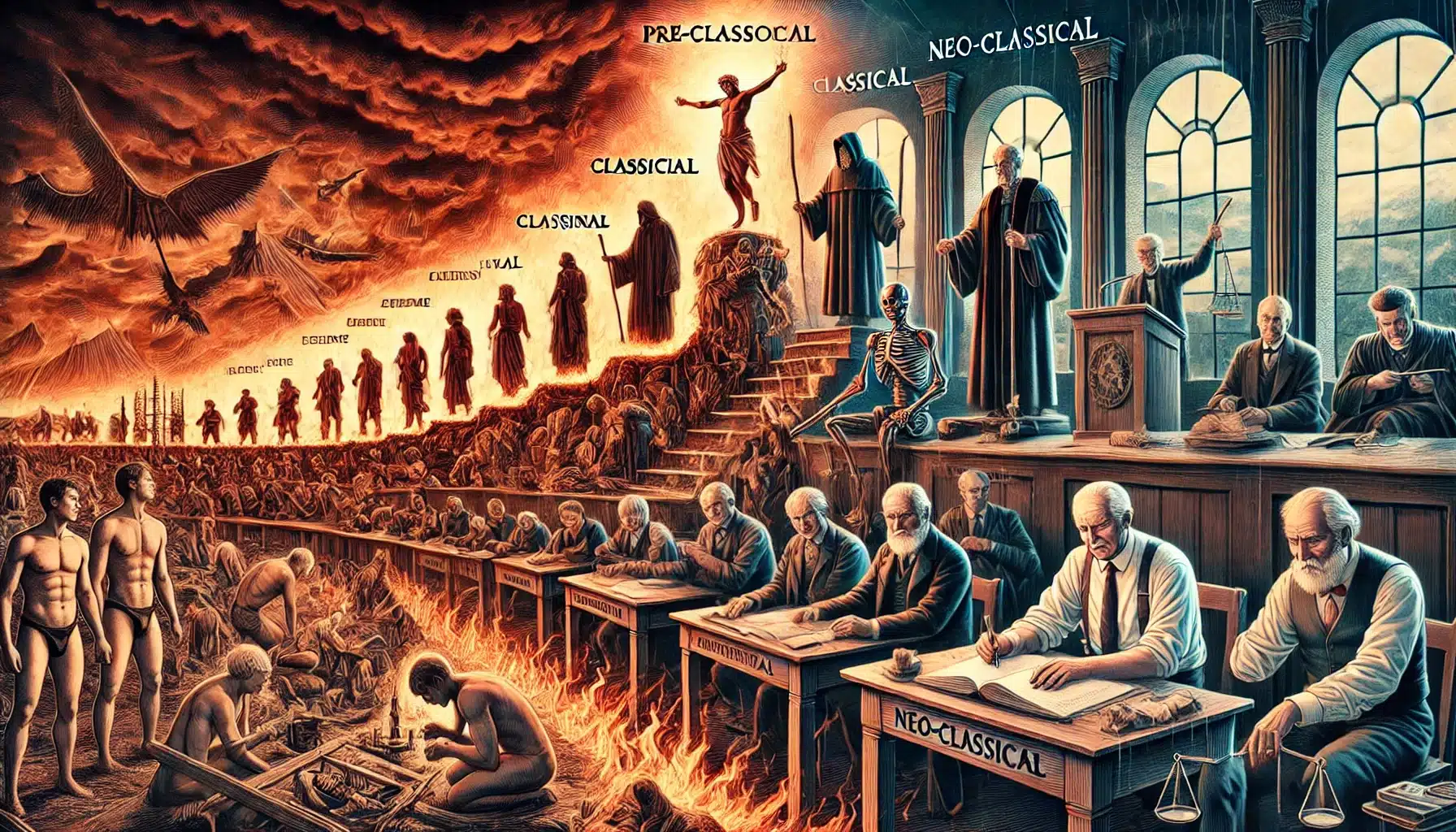

Criminology, rooted in ancient philosophies, has evolved through various schools of thought. The Pre-Classical School linked crime to supernatural forces, while the Classical School, led by figures like Cesare Beccaria, emphasized free will and rational choice in criminal behavior. The Neo-Classical

Deep dive into schools of Criminology in our latest podcast!

Introduction

Criminology dates back to the time of Greek philosophers like Hippocrates, Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. These thinkers attributed criminal behaviour to a corrupted soul, often linked to physical deformities. During primitive societies and the early medieval period, human intellect was largely influenced by religion and superstitions, leading to laws dominated by these beliefs. As a result, legal action was often seen as a last resort, with little consideration given to the mental state or circumstances surrounding the crime. The lack of a fair judicial system led to punishments that were frequently arbitrary and irrational. However, as human thought evolved and modern society emerged, social reformers focused on developing a robust criminal justice system. This effort led to the emergence of criminology as a distinct field of study, shaped by various schools of thought.

Definition of Criminology

Different philosophers have tried to define Edwin H. Sutherland defines criminology as “Criminology is the body of knowledge regarding crime as a social phenomenon. It includes within its scope the process of making laws, breaking laws, and reacting toward the breaking of laws.”[1]

Cressey defined criminology as “the scientific study of the nature, extent, cause, and control of criminal behaviour in both the individual and society.”[2]

Tappan defined criminology as “the study of crime, criminals, and criminal behavior, including the law’s response to crime and criminals, with the ultimate goal of controlling criminal behaviour”[3]

Sellin described criminology as “a study of the social phenomenon of crime, the behavior patterns of criminals, and the means by which society responds to and attempts to control criminal conduct”[4]

Schools of Criminology

During the 18th and 19th centuries, the Schools of Criminology gained prominence.[5] The four major schools are the Pre-Classical School, the Classical School, the Neo-Classical School, and the Positivist School. Each of these schools interpreted criminology based on their own beliefs, customs, knowledge, and the context of their respective eras.[6]

1. Pre-Classical School

The Pre-Classical School, often referred to as the Demonological School, gained prominence in the 17th century in Europe due to the influence of the church and religion. During this period, scientific explanations were not prioritized, and concepts of crime were rooted in superstitions and myths. Criminal behaviour was attributed to external forces, such as spirits or demons, which were beyond human control and understanding. It was believed that criminals were possessed by evil spirits, and punishment was thought to be administered by divine wrath or natural forces.

Offenders underwent various trials, such as battles or being pelted with stones, under the belief that an innocent person would not be harmed—a practice known as the Ordeal Test. This method involved severe torture to determine guilt or innocence. The rationale for these practices was the belief that divine intervention was necessary when human judgment failed. Although such rituals were considered irrational by modern standards, they were widely accepted at the time.

The Demonological Theory, rooted in the belief in the omnipotence of spirits, involved rituals like water and fire ordeals to determine guilt. Over time, as people began to question this theory, scientific inquiry led to the development of the Classical School of Criminology.

2. Classical School

The Classical School of Criminology, led by pioneers like Cesare Beccaria, Jeremy Bentham, and Romilly, marked a shift from the earlier demonological theories. This school posited that individuals act out of free will rather than being driven by evil spirits. It suggested that people commit crimes based on hedonistic motives, seeking to maximize pleasure and minimize pain. Consequently, the Classical School rejected the pre-classical theories.

Beccaria, a key figure in this school, argued that punishments should be proportional to the severity of the crime, critiquing the use of torture as unjust. He believed that torture led to wrongful convictions, as the weak could be coerced into false confessions while the powerful could evade justice due to their social status. Supported by other criminologists, Beccaria’s ideas emphasized deterrence over retribution and focused on the criminal rather than the crime itself.

However, the Classical School had its limitations. It assumed free will as an abstract concept and focused solely on the act of crime without considering the criminal’s state of mind. It also failed to distinguish between first-time and repeat offenders, imposing uniform punishments regardless of the offence’s gravity. Despite these shortcomings, the Classical School’s significant contribution was its advocacy for a fair and consistent criminal justice system, moving away from arbitrary punishments and emphasizing the need to understand the offender’s personality to address the causes of crime.

3. Neo-Classical School

The ‘free will’ theory of the Classical School fell out of favour due to its failure to account for individual differences and its uniform treatment of first-time offenders and habitual criminals alike. The Neo-Classical School emerged as a response, arguing that certain categories of offenders, such as minors, the mentally impaired, or those deemed incompetent, should not be treated the same as prudent individuals when it comes to punishment. These groups were seen as incapable of fully understanding their actions or their consequences.

The Neo-Classical School is praised for advancing the idea that criminal responsibility should take into account the offender’s mental state and personal circumstances. This approach recognizes that criminal acts may occur under specific circumstances that should be considered when assigning liability. Thus, alongside the crime itself, factors such as the offender’s personality, motives, past life, and general character should be evaluated.

Today’s jury system reflects the Neoclassical perspective by offering leniency to those in the aforementioned categories. However, a notable shortcoming of the Neo-Classical School is its view of criminals as societal nuisances that should be expelled, which can be seen as an oversimplification of complex social issues.

4. Positivist School

The earlier criminological schools focused primarily on the crime itself, rather than the criminal. The Positivist School of Criminology, led by Cesare Lombroso, Raffaele Garofalo, and Enrico Ferri, marked a shift towards examining the criminal and the underlying causes of criminal behaviour. Lombroso, a key figure, conducted detailed studies on physical characteristics and concluded that criminals exhibited physical inferiority, which predisposed them to criminal acts. He categorized criminals into three groups: Atavists (or born criminals) who were believed to be inherently predisposed to crime; Insane Criminals, who were unable to comprehend their actions due to mental disorders; and Criminoids, who committed crimes to overcome personal inferiority. Although Lombroso’s theory was influential, it was eventually rejected as the belief grew that no criminal was beyond reformation.

Ferri contributed significantly with his “Law of Criminal Saturation,” which posits that crime results from a combination of physical, anthropological, and psychological or social factors. He categorized criminals into five types: born criminals, occasional criminals, passionate criminals, insane criminals, and habitual criminals. Ferri advocated for crime prevention and offender rehabilitation rather than mere punishment.

Garofalo, another prominent figure, focused on the relationship between criminal behaviour and the lack of moral qualities. He classified criminals into four types: murderers, violent criminals influenced by environmental factors, those lacking moral integrity, and lascivious criminals who commit sexual offenses. His work emphasized the need to address the moral deficiencies leading to criminal behaviour.

Conclusion

Criminology is a well-established field that plays a crucial role in determining the criminal liability of individuals. The various schools of criminology have defined the concept of crime in accordance with the prevailing societal norms and rationalities of their times. Each theoretical framework within criminology has developed its own perspective on the causes of criminal behaviour and has proposed corresponding punishments based on these causes. These theories encompass a range of factors contributing to crime, reflecting diverse viewpoints on the motivations behind criminal acts and the appropriate responses to them.

[1] Sutherland, Edwin H. (1939). Principles of Criminology (3rd ed., p. 3). J.B. Lippincott Co.

[2] Cressey, Donald R. (1955). Criminology (4th ed., p. 22). McGraw-Hill.

[3] Tappan, Paul. (1947). Crime, Justice, and Correction (p. 15). McGraw-Hill.

[4] Sellin, Thorsten. (1938). Culture Conflict and Crime (p. 3). Social Science Research Council.

[5] Unnever, James D., & Gabbidon, Shaun L. (2018). Building a Black Criminology. Volume 24.

[6] Murphy, Tony. (2019). Criminology.