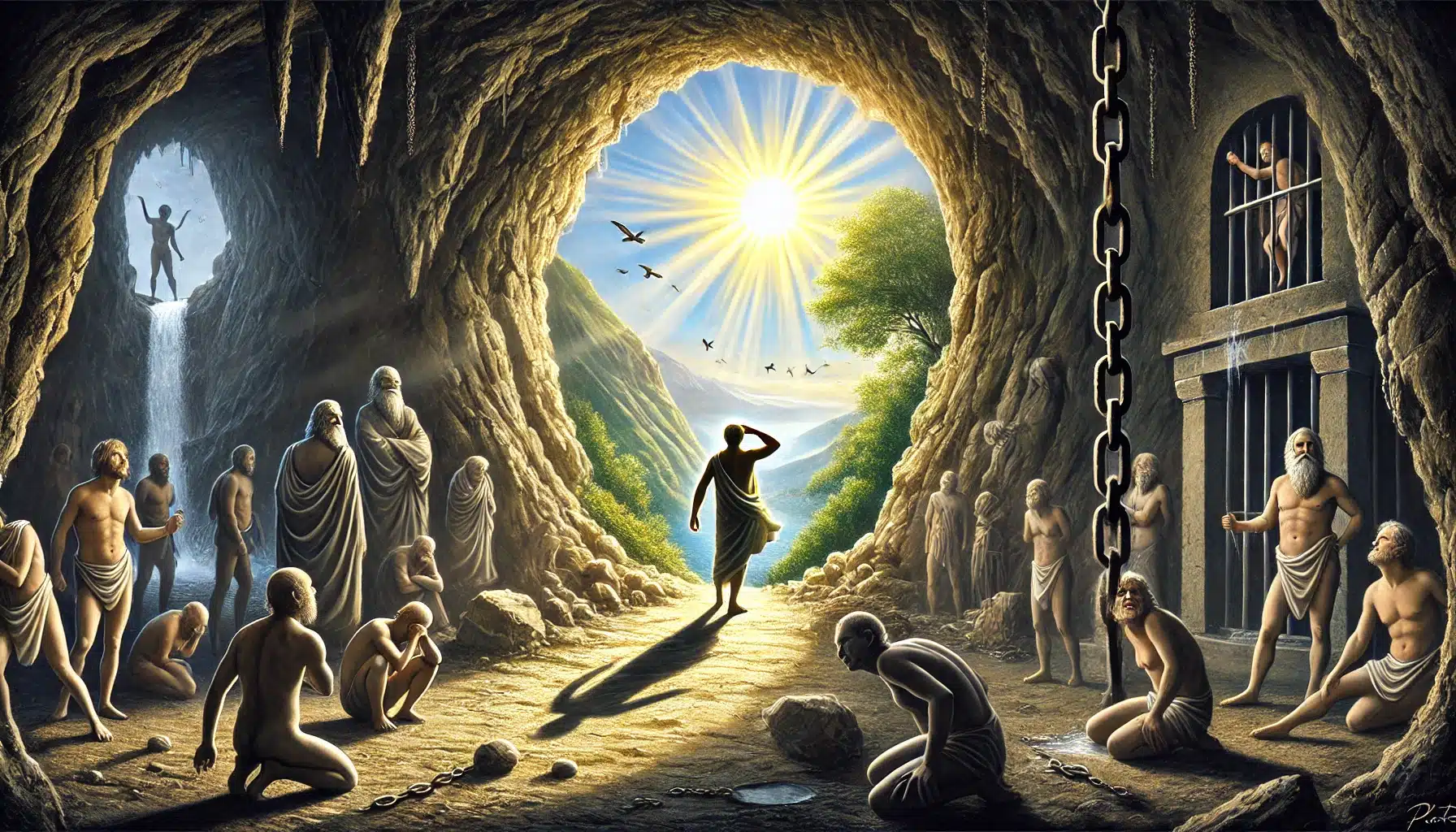

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave illustrates the contrast between perceived reality and true knowledge. In the allegory, prisoners confined in a cave mistake shadows on the wall for reality. When one escapes and encounters the outside world, he realizes that the shadows were mere illusions. Upon returni

Hallucination-resistant legal AI (context engineered)

Introduction

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, from Book VII of The Republic (circa 375 B.C.E.), stands as one of his most famous works and plays a crucial role in his philosophical exploration of knowledge, justice, and the good. The allegory is presented as a dialogue between Socrates and his disciple Glaucon, where Socrates asks Glaucon to imagine people confined in a vast underground cave. These prisoners, chained since birth, face a wall, only able to see the shadows cast by objects behind them, illuminated by a fire. For them, these shadows constitute reality.

Socrates then describes the profound disorientation a prisoner would experience upon being freed. Initially, the prisoner would struggle to comprehend that the shadows were mere illusions and find the reality of solid objects baffling. Upon being exposed to sunlight, the prisoner would be overwhelmed by the brightness but eventually come to appreciate the true forms of the world, including the sun, moon, and stars. This newfound understanding would lead him to pity those still imprisoned, wishing to remain in the light and leave the cave behind.

However, Socrates asserts that for true enlightenment, one must return to the cave, reconnect with the prisoners, and share the knowledge gained. This descent back into darkness symbolizes the philosopher’s duty to apply the understanding of goodness and justice in the world, guiding others towards intellectual and moral awakening.

Theory of Forms

Plato’s Theory of Forms, also known as the Theory of Ideas, posits that the physical world is not as real or as true as timeless, absolute, and unchangeable Forms or Ideas. According to Plato, these Forms are the non-physical essences of all things, of which the objects we perceive in the physical world are mere imitations. In his dialogues, Plato, through characters like Socrates, suggests that these Forms are the only objects of study that can provide true knowledge. This theory addresses the problem of universals by proposing that while physical objects are in constant flux, the Forms themselves are eternal and unchanging, representing the purest essence of various objects and qualities.

Plato argues that every object or quality in reality has a corresponding Form that defines its essence. For example, while there are many individual tables, the Form of “tableness” is the essence that all tables share. Plato’s Socrates asserts that the world of Forms is transcendent, existing beyond our physical world and serving as the essential basis of reality. True knowledge, therefore, is the ability to grasp these Forms with the mind.

Forms, according to Plato, are aspatial and atemporal, meaning they exist outside of space and time. They are perfect, unchanging, and non-physical blueprints of objects and qualities. For instance, while a drawn triangle may be imperfect, it is only through understanding the Form of “triangle” that we recognize the shape. This perfect Form remains constant, regardless of the imperfect representations we encounter.

Plato also explains that our understanding of Forms is limited, as we are always many steps removed from the true idea or Form. The concept of a perfect circle, for instance, cannot be fully captured by any drawn circle or even by the mathematical ratio of pi, as these are only partial representations of the true Form. Thus, the Theory of Forms emphasizes the distinction between the imperfect physical world and the perfect, eternal realm of Forms, which is the true object of knowledge and understanding.

Plato’s conception of Forms indeed varies across his dialogues, and he leaves many aspects of the theory open to interpretation. In the Phaedo, Forms are introduced as familiar concepts without much elaboration. In the Republic, Plato relies on the theory to support his arguments but does not fully explain what Forms are. This lack of detailed explanation has led scholars to various interpretations. Some view Forms as paradigms or perfect examples that the imperfect world models. Others see them as universals, where the Form represents a quality shared by all instances of that quality. Another interpretation suggests that Forms are “stuffs,” representing the totality of a quality across all instances in the visible world. Plato himself recognized the ambiguities in his theory, as seen in his self-critique in the Parmenides

The Allegory of the Cave

Plato’s Allegory of the Cave serves as a profound metaphor for human existence and the contrast between perceived reality and actual truth. The cave represents the limited, shadowy world that people experience through their senses, while the world outside the cave symbolizes the realm of true knowledge and reality.

Prisoners

For the prisoners, the shadows on the cave wall, created by the firelight, constitute their entire reality. However, when one prisoner escapes and encounters the outside world, he realizes that what he once believed to be real is merely an illusion.

Upon returning to the cave, the freed prisoner, now enlightened by the sun, struggles to adjust back to the darkness, and the other prisoners perceive him as having been harmed by the outside world. They remain convinced that their shadowy existence is the only reality worth knowing. This allegory illustrates the tension between knowledge and ignorance, highlighting how people may resist or even fear truths that challenge their deeply held beliefs. The story delves into the human condition, exploring how enlightenment can create a divide between those who understand the deeper truths of existence and those who remain confined to a limited, false reality. Ultimately, it is a commentary on the challenges of seeking and accepting truth, as well as the potential alienation that comes with enlightenment.

Theory of Forms in the Cave

In Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, the stages the prisoner passes through align with the levels of cognition represented on the divided line, which Plato uses to explain the distinction between the visible and intelligible realms. The line is divided into two main sections: the visible realm, which encompasses what we can perceive through our senses, and the intelligible realm, which we can grasp only through the mind.

1. Visible Realm

When the prisoner is in the cave, he exists in the visible realm, where his understanding is limited to the shadows on the wall—mere illusions of reality. This stage corresponds to the lowest level of cognition: imagination. Here, the prisoner is bound, able to perceive only shadows, which symbolize the images and representations from art and culture that shape his understanding of the world. At this stage, he mistakes these shadows for the most real things, unaware that they are merely reflections of true objects.

As the prisoner frees himself and begins to see the objects that cast the shadows—the statues—he reaches the next cognitive stage: belief. This stage represents a step closer to reality, as the prisoner now perceives actual objects, such as people, trees, and other physical forms. However, he still believes these sensible particulars to be the most real, not yet recognizing them as mere copies of the Forms.

2. Intelligible Realm

The prisoner’s ascent from the cave into daylight symbolizes his transition into the intelligible realm, where he encounters the Forms themselves. This stage corresponds to thought, where the prisoner can reason about the Forms but still relies on images and unproven assumptions. He begins to understand that the objects he previously took as real are imperfect copies of more fundamental truths.

Ultimately, the prisoner turns his gaze to the sun, which represents the ultimate Form—the Form of the Good. The Form of the Good is the highest object of knowledge and the source of all other Forms, embodying the essence of goodness, truth, and beauty. Upon grasping the Form of the Good, the prisoner reaches the highest cognitive stage: understanding. At this stage, he no longer needs images or assumptions to aid his reasoning; he comprehends the first principle of philosophy, which explains all existence and knowledge without reliance on prior concepts.

Plato compares the Form of the Good to the sun to illustrate its role in the intelligible realm. Just as the sun provides light and enables sight in the visible world, the Form of the Good illuminates the mind, making knowledge and understanding possible. The sun causes life and growth in the physical world, while the Form of the Good is responsible for the existence and intelligibility of the Forms themselves.

This ultimate understanding is attainable only by the philosopher, who, according to Plato, is uniquely qualified to rule, having transcended the limitations of the visible realm to grasp the true nature of reality.