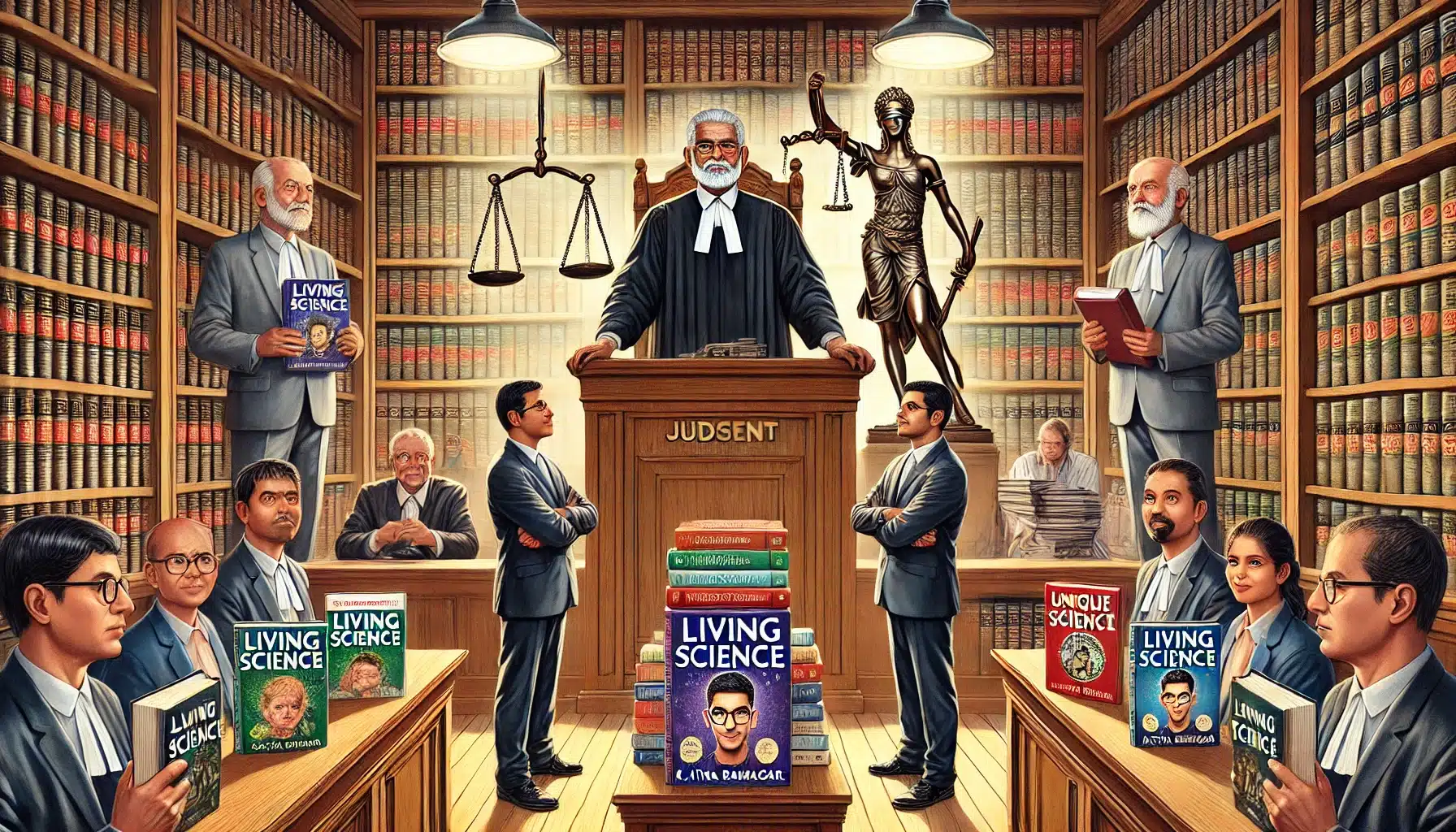

The Delhi High Court in Ratna Sagar Private Limited v. Trisea Publications held that copyright protection extends to the originality in the presentation and expression of material, not just the underlying ideas or concepts. The court found substantial similarities between Ratna Sagar’s “LIVING SCIEN

“Copyright protection extends to original works, even those based on common sources, the originality in the presentation and expression of the material, rather than the underlying ideas or concepts, is what is protected by copyright law.”

Citation: 1997(1)ARBLR30(DELHI), 64(1996)DLT539

Date of Judgement: 20th May, 1996

Court: High Court of Delhi

Bench: K. Ramamoorthy (J)

Facts

- Ratna Sagar, a leading publisher of educational books, claimed copyright ownership in its “LIVING SCIENCE” series.

- Trisea Publications, on the other hand, published a similar series titled “UNIQUE SCIENCE.”

- Ratna Sagar claimed to be the original owner of the copyright in the “LIVING SCIENCE” series, either through creation or assignment. Ratna Sagar alleged that Trisea’s series was a direct copy of its work, infringing upon its copyright.

- Trisea contended that both series were derived from common sources, namely, scientific knowledge and concepts. Trisea claimed that their “UNIQUE SCIENCE” series was an original work, distinct from Ratna Sagar’s “LIVING SCIENCE” series.

- Trisea also argued that Ratna Sagar had acquiesced in their publication, thereby waiving their right to claim copyright infringement.

- The court was tasked with determining whether Trisea’s actions constituted copyright infringement and, if so, what remedies were appropriate.

Decision of the Delhi High Court

The court gave its ruling in favour of Ratna Sagar and granted an interim injunction restraining Trisea from printing, publishing, selling, or offering for sale any infringing works. The court reasoned that Ratna Sagar had established a prima facie case of copyright infringement and that the balance of convenience supported its position.

In its decision, the court carefully analyzed the similarities between the two series. It found that the similarities were substantial and went beyond mere commonalities in subject matter. The court noted that the two series shared similar features such as the organization of chapters, the use of specific examples, and the presentation of certain concepts. These similarities, according to the court, were indicative of copying and not merely the result of independent creation.

The court also rejected Trisea’s claim of common source. While it acknowledged that both series were based on common scientific knowledge, the court emphasized that the way in which that knowledge was presented and expressed in the “LIVING SCIENCE” series was original and protected by copyright law.

Regarding Trisea’s argument of acquiescence, the court found that Ratna Sagar’s delay in taking action did not constitute acquiescence. The court noted that Ratna Sagar had taken steps to protect its copyright, including issuing notices to Trisea and seeking legal advice.

The Court in para 18 of the Judgement clarified that “No doubt the ideas for books both of the plaintiff and the defendants would come from nature but what we are concerned here is, how the things existing in nature were presented by the plaintiff and the defendants. The idea of the configuration of the ideas into the picture and words would form the fulcrum of the work done by any person. Therefore, when it is admitted that the plaintiff had published the work earlier its right must be protected. The argument of Mr. Bansal that the plaintiff has not proved the assignment is not a matter before this Court at this stage and the person aggrieved in the absence of assignment may be the original author, but the defendants cannot be heard to be contended that the plaintiffs have not proved the assignment and, therefore, the defendants are free to infringe the copyright of the plaintiff. Their case on the other hand, in the absence of the assignment as contended by the learned Counsel Mr. Bansal should be that the original authors had concluded to the act of the defendants and, therefore, the plaintiff cannot seek to espouse the cause of the author. The plaintiff claims absolute right in the copyright, by virtue of the assignment and also as registered owner after the assignment. Therefore, on the facts and in the circumstances of the case, I have no hesitation in coming to the conclusion that the defendants are guilty of infringing the copyright of the plaintiff in the books and the plaintiff has made out a prima facie strong case for granting injunction. The balance of convenience is also in favour of the plaintiff.”

Key legal issues discussed

1. Is copyright protection available for educational materials derived from common sources?

Yes

While common sources may be used, the originality in the presentation and expression of the material is protected by copyright law.

2. Can a plaintiff claim copyright ownership based on prior publication alone?

No

Prior publication alone does not confer copyright ownership. The plaintiff must also establish ownership through assignment or creation. This is a fundamental requirement under Section 19 of the Indian Copyright Act, 1957, which specifies that copyright ownership can be assigned in writing.

3. Is copyright infringement established by mere similarity between two works?

No

Similarity alone is not sufficient to establish infringement. There must be substantial similarity and a causal connection between the infringing work and the copyrighted work. The court carefully analysed the similarities between the two series and found that they were substantial and indicative of copying.

4. Can a defendant claim fair use as a defense to copyright infringement?

Yes, but fair use is a narrow exception.

Section 52 of the Copyright Act of 1957 in India defines fair use and fair dealing as exceptions to copyright infringement. Fair use is the use of copyrighted material without the copyright owner’s consent for certain purposes, such as Criticism or review of the work or another work; Reporting on current events, including public lectures; Reproducing the work in a newspaper, magazine, or other periodical for news reporting; Broadcasting, filming, or photographing; Teaching, scholarship, or research; Transformative work; Quoting a few lines from a play; Sharing a video parody of a song online; Non-profit educational uses etc.

The court must consider factors such as the purpose and character of the use, the nature of the copyrighted work, the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and the effect of the use on the potential market for the copyrighted work.