In Donoghue v. Allied Newspapers Ltd. (1937), the UK High Court ruled that Steve Donoghue, who provided ideas and stories, did not own the copyright in articles written by journalist Mr. Felstead. The court held that copyright protection applies to the specific form of expression, not to the underly

“Mere transcribing and typing do not make anyone entitled to own a copyright in respect of what he has typed or transcribed. The owner of the copyright is the author of the work who dictates.”

Citation: (1937) 3 All ER 503

Date of Judgment: 6th July, 1937

Court: U.K. High Court

Bench: Farwell (J)

Facts

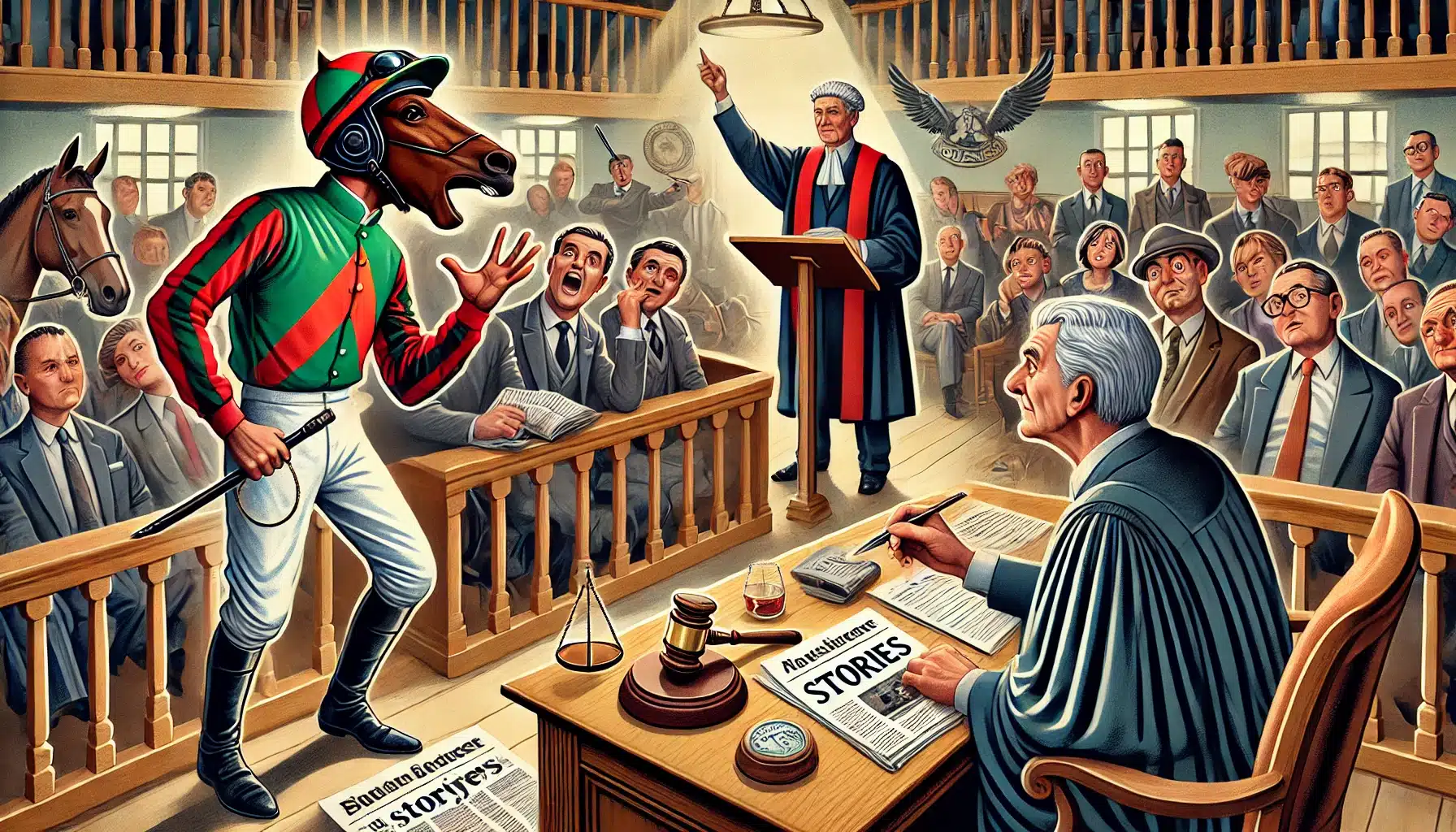

- In 1931, the News of the World newspaper, seeking to publish a series of articles entitled “Steve Donoghue’s Racing Secrets,” employed freelance journalist Mr. Felstead. Steve Donoghue, a renowned racing jockey, did not write the articles himself but instead communicated his adventures and experiences to Felstead. Felstead then wrote the articles based on Donoghue’s accounts, which were reviewed and revised by Donoghue before publication. The series appeared weekly in the News of the World.

- In 1936, Felstead entered into an agreement with another newspaper, Guides and Ideas, to publish an article titled “My Racing Secrets by Steve Donoghue.” This article was a modified version of the original series, with shortened content and new material added.

- Felstead did not seek permission from Donoghue to reuses this. Donoghue, alleging infringement of his work, sought an injunction to prevent the publication of the new article.

- Donoghue contended that he was the rightful owner of the copyright in the articles published by the News of the World. He argued that since the original articles were based on his personal experiences and were reviewed and altered by him before publication, he should have been credited with the copyright.

- Donoghue claimed that Felstead’s subsequent publication of a modified version without permission constituted an infringement of his copyright.

- Felstead and Guides and Ideas argued that copyright ownership did not belong to Donoghue. They asserted that Felstead, as the person who transcribed and composed the articles based on Donoghue’s verbal communications, was the author and, thus, the owner of the copyright. They contended that merely transcribing Donoghue’s ideas did not entitle him to copyright ownership.

Decision of the High Court

The court ruled in favor of the defendants, holding that Steve Donoghue was not the owner of the copyright in the articles. The court’s decision was based on the reasoning that copyright protection is granted to the author of the work as expressed in a tangible form, not merely the originator of the ideas.

Justice Farewell of the High Court observed that copyright does not extend to ideas themselves. He noted that while a person may conceive a brilliant idea for a story, picture, or play and consider it original, copyright protection is not granted to the idea alone. Instead, copyright subsists in the tangible form in which the idea is expressed, such as through a written work, picture, or play. Therefore, if an individual communicates their idea to an author, artist, or playwright, the copyright belongs to the person who has transformed the idea into a tangible form, not to the originator of the idea.

In the present case, the court determined that although Mr. Donoghue supplied the stories and ideas, the language used in the articles was Mr. Felstead’s, not Donoghue’s. Justice Farewell highlighted that aside from the embellishments provided by Felstead, the particular form of language used to convey the stories was Felstead’s creation. The court cited Evans v. Hulton & Co. Ltd[1] to reinforce that copyright subsists in the specific expression of the work, not in the underlying ideas or themes. In Evans v. Hulton & Co. Ltd, it was established that the person who writes the text holds the copyright, even if the ideas are provided by someone else. This precedent underscored that the right to copyright resides with the creator of the textual expression rather than the source of the ideas.

Justice Farewell noted that while Mr. Donoghue provided the substance of the articles, the actual expression and language were Felstead’s work. The judge found that similar to the Evans v. Hulton case, where the foreign contributor was not considered a joint author due to his lack of involvement in the literary expression, Mr. Donoghue did not contribute to the language or literary form of the articles.

Consequently, the court concluded that Mr. Donoghue was neither the sole nor co-author of the articles published by News of the World. As such, his claim for copyright infringement was deemed unsustainable, and the action was dismissed with costs.

Key legal issues discussed

1. Is Mr. Donoghue the sole or joint owner of the copyright in the articles published in the News of the World?

No

The court ruled that Mr. Donoghue did not own the copyright in the articles. Although he provided the ideas and substance for the articles, Mr. Felstead, who transcribed and wrote them up, was considered the author of the specific expression of those ideas. The court concluded that copyright exists in the particular form of expression, not in the underlying ideas. The language and structure of the articles were the work of Mr. Felstead, and Mr. Donoghue’s contributions were not sufficient to establish joint authorship.

2. Who is the copyright owner when a work is created through verbal communication and transcription?

Felstead

The court decided that the copyright owner is the person who actually transcribes or creates the written work. In this case, since Felstead transcribed and composed the articles based on Donoghue’s spoken accounts, Felstead was deemed the author and copyright holder.

3. Can copyright be claimed over ideas or concepts communicated to a writer?

No

Copyright protection does not extend to ideas or concepts themselves. The court clarified that copyright exists in the specific expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves. Mr. Donoghue’s ideas, although valuable and original, were not protected by copyright until they were fixed in a tangible form by Mr. Felstead. Thus, Donoghue’s communicated ideas did not grant him copyright over the articles; the protection was only for the form in which Felstead expressed those ideas.

4. Does merely communicating ideas to a writer grant copyright to the communicator?

No

Communicating ideas to a writer does not automatically grant copyright to the communicator. Copyright protection is assigned to the particular form of expression created by the writer or transcriber. In this case, Mr. Donoghue’s communication of ideas did not endow him with copyright over the articles. The copyright was held by Mr. Felstead, who expressed those ideas in the form of written articles. The court’s decision reinforced that copyright is concerned with creative expression rather than the underlying ideas.

5. Who holds the copyright in a literary work when the ideas are provided by one person but the written expression is created by another?

Felstead

Copyright is held by the person who writes the actual text of a literary work. In this case, Mr. Felstead, who wrote the articles based on Mr. Donoghue’s oral content, held the copyright. The law protects the specific form of expression—the written text—rather than the underlying ideas. Mr. Donoghue only provided ideas and did not contribute to the written text.

6. Does the republication of articles without consent constitute copyright infringement if the original author does not hold copyright?

No

If the original author does not hold copyright, republication does not constitute copyright infringement. Since Mr. Donoghue did not hold the copyright, the republication of the articles by Mr. Felstead did not infringe any copyright rights. The right to prevent republication depends on holding the copyright, which Mr. Donoghue did not have.

7. Does a contract involving the provision of material for articles imply the transfer of copyright?

No

A contract for providing material does not automatically transfer copyright unless explicitly stated. In this case, the contract between Mr. Donoghue and the News of the World focused on material provision and payment, without specifying a transfer of copyright. Since Mr. Felstead wrote the articles, he retained the copyright, and the contract did not imply a transfer of copyright from Mr. Donoghue to the News of the World.

[1] [1924] All ER Rep 224.