Addagada Raghavamma and Another v. Addagada Chenchamma and Another

Citation: AIR 1964 SC 136, [1964] 2 S.C.R. 933

Bench: K. Subba Rao, J.R. Madholkar, Raghubar Dayal

Date of Judgement: 9 April, 1963

Facts:

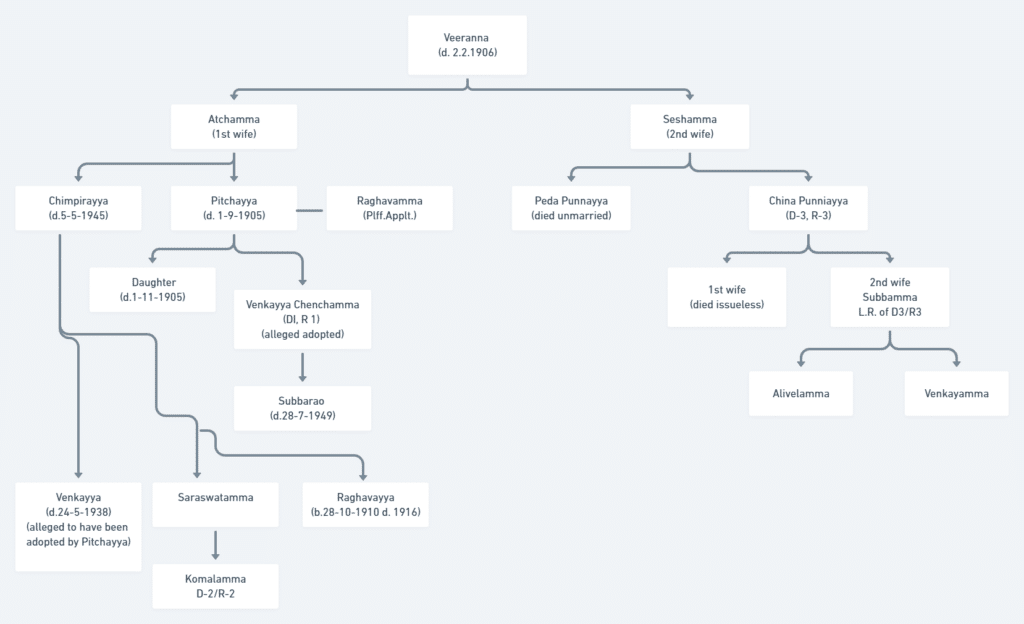

A person named Veeranna had two wives and that Chimpirayya and Pitchayya were his sons by the first wife and Peda Punnayya and China Punnayya were his sons by the second wife. Veeranna died in the year 1906 and his second son Pitchayya had predeceased him on 1.9.1905 leaving his widow Raghavamma. It is alleged that sometime before his death, Pitchayya took Venkayya, the son of his brother Chimpirayya in adoption; and it is also alleged that in or about the year 1895, there was a partition of the joint family properties between Veeranna and his four sons, Chimpirayya, Pitchayya, Peda Punnayya and China Punnayya, Veeranna taking only 4 acres of land and the rest of the property being divided between the four sons by metes and bounds.

Venkayya died on May 24, 1938, leaving behind a son Subbarao. Chimpirayya died on May 5, 1945 having executed a will dated January 14, 1945 whereunder he gave his properties in equal shares to Subbarao and Kamalamma, the daughter of his predeceased daughter Saraswatamma; thereunder he also directed Raghavamma, the widow of his brother Pitchayya, to take possession of the entire property belonging to him, to manage the same, to spend the income therefrom at her discretion and to hand over the property to his two grandchildren after they attained majority and if either or both of them died before attaining majority, his or her share or the entire property, as the case may be, would go to Raghavamma. After the death of Chimpirayya on 05.05.1945 Raghavamma allowed Chenchamma to manage the entire property and she accordingly came into possession of the entire property.

Subbarao died on July 28, 1949. Raghavamma filed a suit on October 12, 1950 in the Court of the Subordinate judge, Bapatlal, for possession of the plaint scheduled properties; and to that suit, Chenchamma was made the first defendant; Kamalamma, the second defendant; and China Punnayya, the second son of Veeranna by his second wife, the third defendant.

The first defendant denied that Venkayya was given in adoption to Pitchayya or that there was a partition in the family of Veeranna in the manner claimed by the plaintiff. She averred that Chimpirayya died undivided from his grandson Subbarao and, therefore, Subbarao became entitled to all the properties of the joint family by right of survivorship. She did not admit that Chimpirayya executed the will in a sound and disposing frame of mind. She also did not admit the correctness of the Schedules attached to the plaint.

Lower Court´s decision:

The learned Subordinate Judge, after considering the entire oral and documentary evidence in the case, came to the conclusion that the plaintiff had not established the factum of adoption of Venkayya by her husband Pitchayya and that she also failed to prove that Chimpirayya and Pitchayya were divided from each other; and in the result, he dismissed the suit with costs.

High Court´s decision:

On appeal, a Division Bench of the Andhra High Court reviewed the entire evidence over again and affirmed the findings of the learned Subordinate judge on both the issues. Before the learned judges another point was raised, namely, that the recitals in the will disclose a clear and unambiguous declaration of the intention of Chimpirayya to divide, that the said declaration constituted a severance in status enabling him to execute a will. The learned judge rejected that plea on two grounds, namely, (1) that the will did not contain any such declaration; and (2) that, if it did, the plaintiff should have claimed a division of the entire family property, that is, not only the property claimed by Chimpirayya but also the property alleged to have been given to Pitchayya and that the suit as framed would not be maintainable.

Appeal to Supreme Court:

The appellant/plaintiff preferred the appeal by certificate to the Supreme Court which was dismissed after taking into consideration the Hindu Law texts and a variety of privy council´s judgments on the same subject matter.

Key Legal Issues discussed in the case:

1. Whether the conditions under Art. 133 of Constitution for granting a certificate of appeal by the High Court also limits the scope of appeal with regards to the issues raised involving substantial question of law?

Under Art. 133 of the Constitution the certificate issued by the High Court in the manner prescribed therein is a precondition for the maintainability of an appeal to the Supreme Court. But the terms of the certificate do not circumscribe the scope of the appeal, that is to say, once a proper certificate is granted, the Supreme Court has undoubtedly the power, as a court of appeal, to consider the correctness of the decision appealed against from every standpoint, whether on questions of fact or law. A successful party no doubt can question the maintainability of the appeal on the ground that the certificate was issued by the High Court in contravention of the provisions of Art. 13 3 of the Constitution, but once the certificate was good, the provisions of Art. 133 did not confine the scope of the appeal to the certificate.

Scope of review findings of facts: where the findings are such that it “shocks the conscience of the Court or by disregard to the forms of legal process or some violation of some principles of natural justice or otherwise substantial and grave injustice has been done.”

2. What constitutes severance in status from Joint Hindu Family?

The general principle undoubtedly is that a Hindu family is presumed to be joint unless the contrary is proved, but where it is admitted that one of the coparceners did separate himself from the other members of the joint family and had his share in the joint property partitioned off for him, there is no presumption that the rest of the coparceners continued to be joint. There is no presumption on the other side too that because one member of the family separated himself, there has been separation with regard to all. It would be a question of fact to be determined in each case upon the evidence relating to the intention of the par ties whether there was a separation amongst the other coparceners or that they remained united. The burden would undoubtedly lie on the party who asserts the existence of a particular state of things on the basis of which he claims relief.”

3. Whether an unequivocal recitals in Will declaring intention to divide will constitute severance in status without the knowledge of the affecting coparceners?

A Will speaks only from the date of death of the testator. A member of an undivided coparcenary has the legal capacity to execute a will; but he cannot validly bequeath his undivided interest the joint family property. If he died an undivided member of the family, his interest survives to the other members of the family and, therefore. the will cannot operate on the interest of the joint family property. Further in order to the answer the question, reference was made to the Hindu Law text and the issue was analysed on two points i.e. declaration of intention and communication of it to other affected thereby. It was quoted in Saraswati Vilasa, placitum 28 : “From this it is known that without any speech (or explanation) even by means of a determination (or resolution) only, partition is effected, just as an appointed daughter is constituted by mere intention without speech.” Hence, declaration of unequivocal intention creates the severance in status as supported by the Mitakshara law because severance is a state (or condition) of mind and declaration is only a manifestation of this mental state. As declaration or manifestation can´t take place in vaccum and declare is to assert to others or make known, hence those others should be the affected one´s. After a long line of decisions, it was authoritatively laid down the proposition that the knowledge of the members of the family of the manifested intention of one of them to separate from them is a necessary condition for bringing about that member’s severance from the family.

4. Whether the knowledge of intention to severe dates back to the date of declaration?

The doctrine of relation back has already been recognized by Hindu Law as developed by Courts and applied in that branch of the law pertaining to adoption. There are two ingredients of a declaration of a member’s intention to separate. One is the expression of the intention and the other is bringing that expression to the knowledge of the person or persons affected. When once that knowledge is brought home that depends upon the facts of each case it relates back to the date when the intention is formed and expressed. But between the two dates, the person expressing the intention may lose his interest in the family property; he may withdraw his intention to divide; he may die before his intention to divide is conveyed to the other members of the family: with the result, his interest survives to the other members. A manager of a joint Hindu family may sell away the entire family property for debts binding on the family. There may be similar other instances. If the doctrine of relation back is invoked without any limitation thereon, vested rights so created will be affected and settled titles may be disturbed.s the doctrine of relation back involves retroactivity by parity of reasoning, it cannot affect vested rights. It would follow that, though the date of severance is that of manifestation of the intention to separate, the rights accrued to others in the joint family property between the said manifestation and the knowledge of it by the other members would be saved.